You’re Gonna Be a Star Someday

Part 1: The Triumphant Team

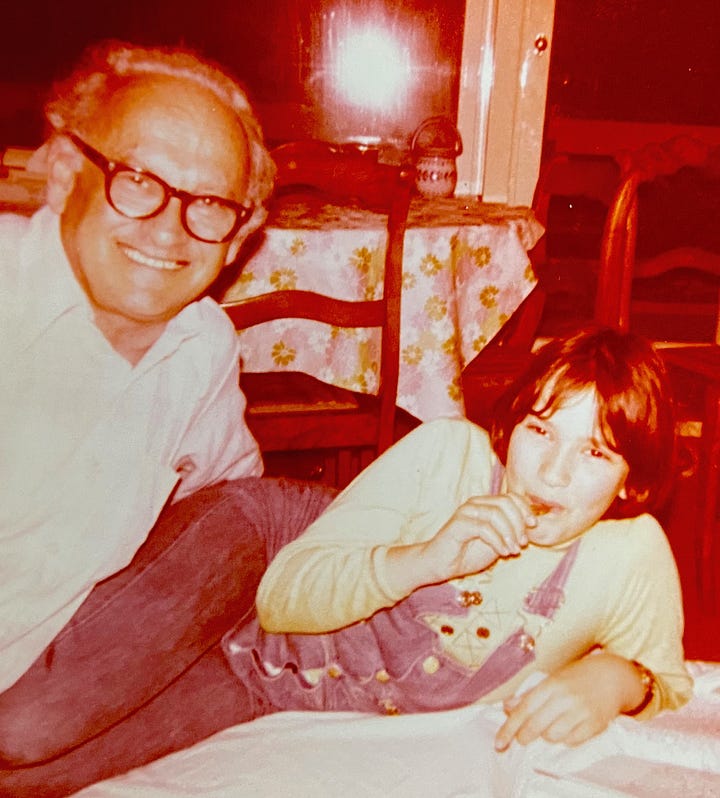

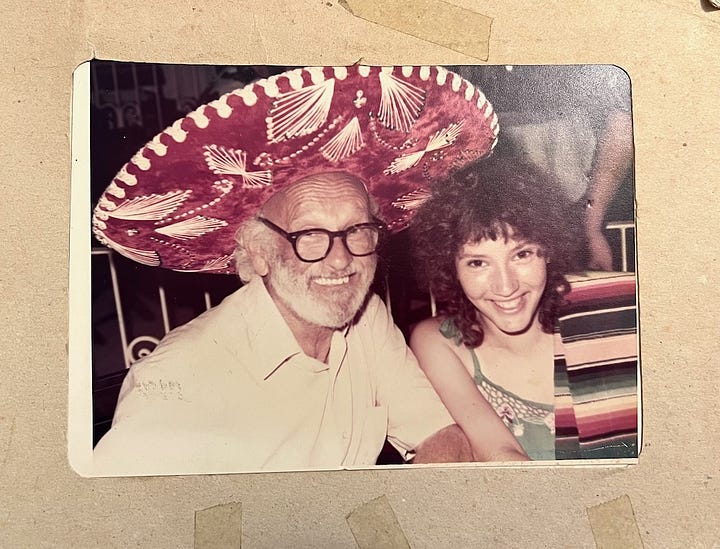

My Vati (pronounced FAH-tee, German for Daddy) believed that when I grew up, I’d be a star. As a child, I believed it too.

My Vati loved to show off his kids. From an early age, my brother Lennie sang and played piano and violin. I sang and played piano and danced. When guests came over, we performed for them. Everyone clapped and praised us.

My parents separated when I was seven. After that, I spent the school years with my Vati in Lawrence, Kansas, and summers with my mom in Berkeley, California. My two oldest brothers, Bernie and Ronnie, were already out of the house by then. A year after my parents’ separation, my brother Lennie moved to Berkeley to live with my Mom. From then on, it was Vati and me. A Daring Duo. A Triumphant Team.

The song my Vati most loved to hear me sing when I was growing up was Helen Reddy’s Keep On Singin’, about a single dad raising his talented daughter. There aren’t many songs that pay tribute to the father-daughter bond the way that one does. I have countless memories of Vati asking me to sing it, both for him and for others. He was virtually tone deaf, but he’d tap his feet enthusiastically and mouth the words as I sang, in the character of the father addressing his daughter, Keep on singin’, don’t stop singin’, you’re gonna be a star someday. You’re gonna make a lot of people happy when they come to hear you play…

I sang Keep on Singin’ at my first audition, when I was eight. The show was Oklahoma! The University of Kansas had an excellent theatre program, and every summer they put on a big musical and invited the community in my hometown of Lawrence to audition.

I knew nothing about auditioning. I had no headshot or resumé. There was a form where we listed our experience and conflicts. I had only my school choir and ballet lessons to list. I had lots of experience performing in my living room, though, and I was not afraid.

The audition was held in Murphy Hall, a thousand-seat theatre that was the mainstage for university productions. I’d seen my brother Len perform there in the opera La Bohème a few years earlier. I was excited to get up on that big, wide stage.

I didn’t bring sheet music. I climbed the steps to the stage, then walked up to the pianist and asked if he knew Keep on Singin’. He did not.

I strode to center stage and said, “He doesn’t know this.”

This garnered a friendly laugh from the auditors.

I sang the whole song a cappella—all three verses and choruses. No one stopped me. Vati sat in the audience. He told me on the way home that he’d watched the auditors’ faces, and he could tell they were smitten.

We rejoiced when I was cast in the chorus—the only role available to a child.

During rehearsals, I memorized the entire show. I’d stand backstage, mouthing the words of every scene. The adult actors smiled at me, shaking their heads in amazement. They all told me how smart I was, how talented. I became very close with the other kids in the cast. We pretended we were a family. A grad student in the theater department who played Curly was our dad.

From the beginning, I was drawn to the character roles. I much preferred the plucky, flirty character of Ado Annie to the sweet, slightly insipid Laurie whose romantic story is at the center of the show. I fantasized that the actress playing Ado Annie, who happened to be my beloved school music teacher, would get sick during dress rehearsals. Not deathly ill, just sick enough to knock her out of the performances. The director would put his head in his hands, crying, What are we going to do? We’ll have to cancel the show!

At that point in my fantasy, one of the actors would say, Wait a minute! Tanya knows all the lines!

Great idea! The director would say.

He’d put me in, and the crowd would adore me. They’d hoot and whistle as I strutted the stage, singing, I’m just a girl who cain’t say no. When I took my bow during curtain call, they’d jump to their feet. Vati would be right there in the front row, clapping ecstatically, his eyes shining with pride. The whole cast would thank me for saving the day. It never once occurred to me that they wouldn’t cast an eight-year-old child opposite adult actors, even if the role had not involved copious amounts of kissing.

The roles kept coming. I played a gingerbread child in the KU Music Department’s opera of Hansel and Gretel. A few months later, my elementary school announced auditions for a production of Oliver!

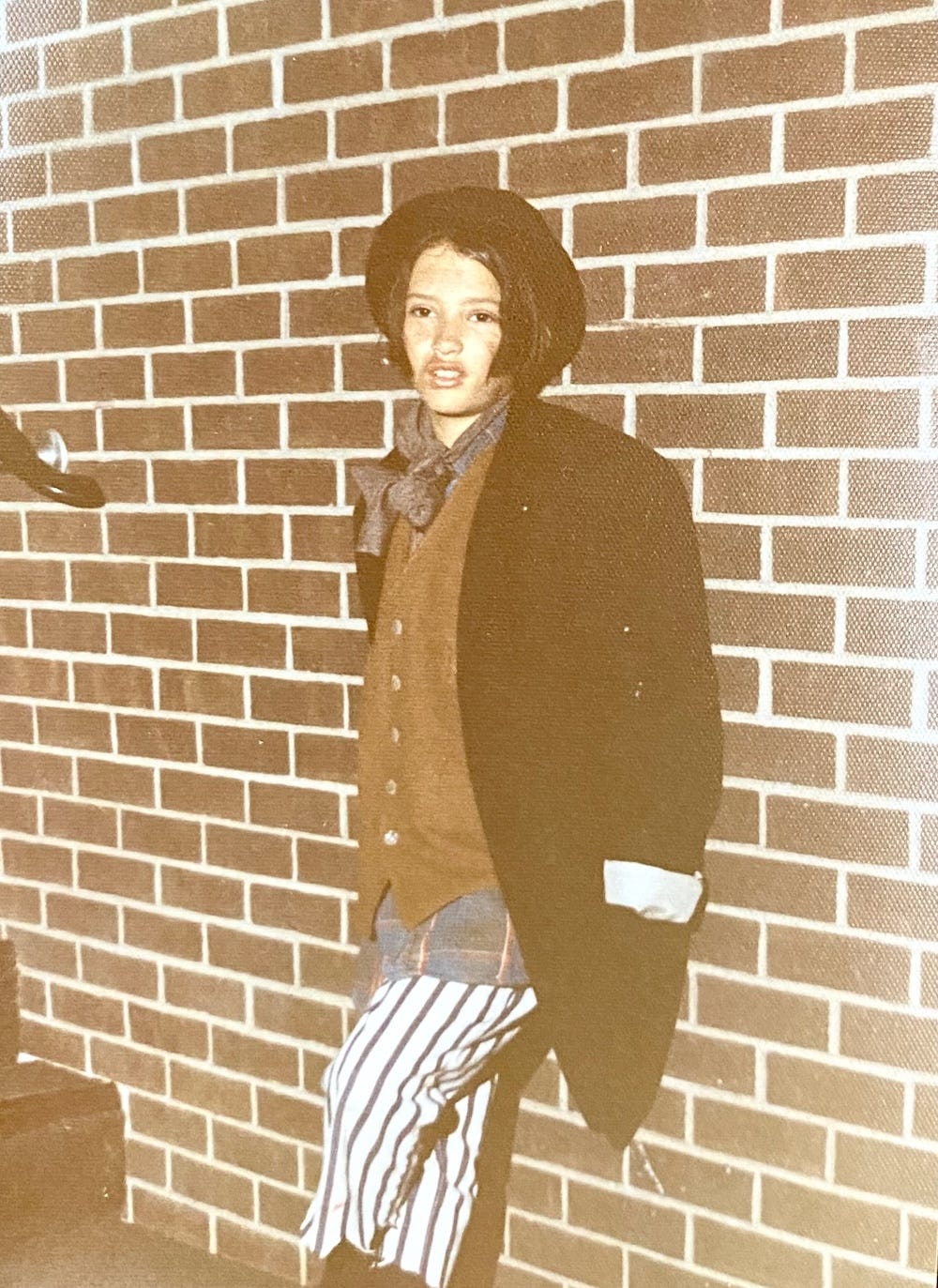

I told Vati I wanted to play the Artful Dodger. Though he was usually 100% supportive of my ambitions, he cautioned me not to get my hopes up, since the part was written for a boy. I got the part, and it became one of my Vati’s favorite stories to tell when boasting of my theatrical accomplishments.

“She was nine years old,” he would crow to whichever friend or family member he was currently regaling. “I told her, ‘Tanya, that’s a boy’s role!’ She said, ‘I’m going to get it anyway.’ And she did!”

What did I love about it, exactly? Was it all the attention and adulation that came my way? The thrill of being privy to a grown-up world? The deep sense of camaraderie among the cast? Yes, yes and yes. Add to that the sheer fun of singing and dancing, the pleasure of spending so much time with music and stories I came to love, and the potent magic of creating a world onstage and inviting the audience in. Plus, it made my Vati so happy! It’s no wonder I kept going.

Years later, as an adult pursuing a career in theatre, I’d spend a lot of energy interrogating my motives for continuing to act. I’d ask myself whether it was art or ego that kept me plugging away in that insecure, underpaid, highly competitive industry. Art, I felt, was a worthy motivation. Ego was not.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

As a child, I never lost a part. I had good pitch, a strong voice, and boatloads of confidence. I was emotionally elastic and unafraid to go big. On top of that, I was an excellent cold reader.

Since I lived in Lawrence, Kansas, not New York or Los Angeles, opportunities were limited. Nevertheless, from the time I first trod the boards until the time I left for college, there was never a window of more than a few weeks in which I wasn’t either rehearsing or performing.

Whether it was a school performance, community theatre, a KU production, or something at the large Jewish Community Center an hour away in Kansas City, my Vati was in the audience at every show, cheering me on. Nothing made him prouder than having people come up to him after the show and gush about what a phenom I was.

In junior high, the competition started to catch up. The first time I lost a role, it was a crash course in humility.

In seventh grade, my school was doing a production of You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown, and I was angling for the role of Snoopy. Although I read for it in a couple of callbacks, the role ultimately went to my childhood friend Becca, who’d played Nancy in our elementary school production of Oliver! a few years before. Her mom—an English teacher at the school and the head of the drama club—was directing the show.

My Vati was livid. Of course she would cast her daughter! It wasn’t fair—she should have recused herself! It was an obvious case of nepotism.

Although I railed alongside him about the unfairness of the situation, I had to acknowledge in my heart of hearts that Becca made a fabulous Snoopy. Her smooth alto voice sailed to notes that had landed awkwardly in my vocal break, and her flexible, loose-limbed physicality hilariously captured Snoopy’s determined dogginess.

I ate humble pie and joined the chorus, which had been added to the small-cast show so that more kids could participate.

I remember Vati driving me around town in Sir George—our cream-colored Chrysler LeBaron—to check the bulletin boards when cast lists were announced. That’s how we did things in those days. Vati was always as anxious as I was to see whether my name would appear beside the role I coveted. When I got it, we celebrated together. When I didn’t, we ranted and mourned.

At some point in high school the depth of my father’s investment in my theatrical endeavors started to bother me. During my junior and senior years at Lawrence High, I enrolled in a couple of classes at KU, which allowed me to finagle my way into regular theatre department productions, where I competed against college students. I remember being sixteen and standing in the hallway beside the green room at KU, looking at the cast list for the musical Hair. My name wasn’t on it.

On the car ride home, I sobbed inconsolably. My dad tried to comfort me by saying they were fools not to cast me, since I was obviously the best. He speculated that they needed to spread the wealth among the less gifted of the college students, who after all needed to be cast sometimes too.

“Stop it!” I sobbed. “You don’t know that! You didn’t even see the others!”

He didn’t have to see them, he told me. He knew I was the best.

I felt a flash of anger. “Stop saying that!” I yelled. “It’s not true! You just … You love me too much!”

In my memory, the scene ends there, as if the lights went to black after I spoke those words. I have no memory of his reaction. But I remember saying that—You love me too much—and feeling that the words had been building within me for quite a while. That it was somehow too much. I knew he didn’t see things clearly when it came to me. That his idea of my greatness was not rooted in objective reality. And that it was hard enough carrying my own fierce hopes and disappointments without having to carry his as well.

As a mother myself—my sons are sixteen and twenty-one—I have tremendous empathy for the distress my Vati must have felt as I went about my wild, dramatic process of grieving the roles I failed to get. I know now that there’s nothing more painful than witnessing your children’s suffering and knowing you can’t fix it.

Looking back, it’s easy to say that my Vati should have helped me build the resilience a life in the theatre requires—or any life, for that matter—by conveying the message, Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose—just keep working hard and doing your best, as opposed to, You’re the best there is, and if anyone doesn’t see that they’re flat out wrong. I’ve learned, though, there’s not much value in faulting your parents for being the very human creatures that they were.

My Vati had a kind of innocence about him. In his eyes, I was perfect in every way. That’s all he saw, and nothing I said could convince him otherwise. And although it’s easy to say he set me up for some brutal disappointments in the years to come, I could also say that his belief in me gave me the underlying confidence to withstand them.

P.S. I don’t believe there’s such a thing as too much love.

You can find Part 2 of my journey HERE, in which I head off to college and begin the long, knotty process of questioning my theatrical calling, even as I continue to perform.

For an introduction to my beloved Vati, who suffered tremendous loss and displacement and still remained the most life-loving person I ever knew, check out The Exuberant Professor. You might also enjoy Sunrise Sunset: A Lyric Essay (about my parents’ divorce), The Road Between Us (about the aftermath of my parents’ split), On Forgiveness (about his extraordinary capacity to give others grace); and The Night I Made My Father Cry.

IN OTHER NEWS:

We’ve got just THREE SPOTS LEFT in Rejuvenate & Create in Greece, a Transformational Women’s Writing Retreat on the Island of Amorgos, taking place in October, led by the marvelous author Kelly Dwyer and me. Join us!

Oh Tanya! I was there in the living room with you as you sang and danced your young heart free. A relatable tale! My mama Aggie loved me the same stubborn intense way that dear Vati showered love on you. If it's ok, I'd like to send a relating of my own..So many deep thanks for the Wed. morning storytime with you and fellow scribes♡

Dear Artful Dodger, This is a beautiful piece about you and your musical acting journey and your Vati.

With much admiration , the Strawberry Seller

PS Wait, who acted Ado Annie?!