Where I Have to Go

"You're Gonna Be a Star Someday," Part 2

This piece follows You’re Gonna Be A Star Someday, Part 1 (about my childhood performing in Kansas). You can also read it on its own.

“I learn by going where I have to go.”

- Theodore Roethke, The Waking

During my senior year of high school, I told everyone who would listen that I wanted to attend a large university in a big city with an excellent musical theatre program.

Then I chose a college with none of those characteristics.

We humans like to think we know why we do things. We don’t. The mechanisms by which we make decisions are a lot less logical than we’d like to believe. Countless studies have shown that we decide things first and make up reasons afterwards.

I don’t remember how I justified to myself applying to Oberlin when it was so different from what I’d said I wanted. I do remember that I visited a cousin of mine there, and it felt like home.

Don’t get me wrong: Oberlin College was a wildly creative place. We had solid theatre and dance programs and the chance to study voice at the world-class Oberlin Conservatory of Music. Many of my drama classmates went on to careers in theatre and film. But it was not a pipeline to the New York stage in the mode of, say, an NYU or a Carnegie Mellon. The Conservatory had a classical bent, and the dance department offered only modern and ballet. Neither the Theatre and Dance Program nor the Conservatory produced musicals, although there was an active student-led theatre organization that stepped in to fill the void.

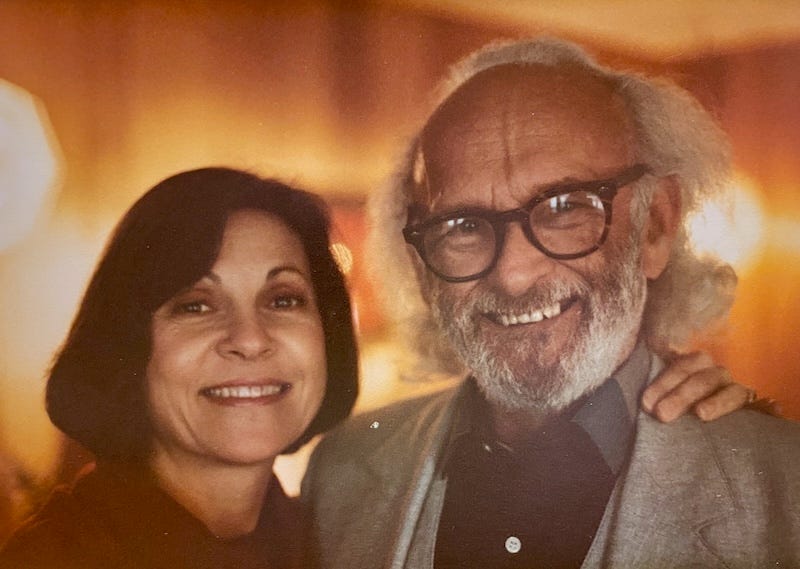

Although my Vati (pronounced FAH-tee, German for Daddy) remained convinced I was destined for stardom, he supported my choice to attend Oberlin, just as he supported pretty much everything I did. He believed in a well-rounded education, regardless of future career. And as a life-long activist, he took great pride in Oberlin’s progressive history as both the first racially integrated and the first co-ed college in the US.

Though I was excited to go away to college, I worried about leaving Vati alone. It had been close to four decades since he’d lived on his own, with neither a spouse nor any of his four children for company. For the past nine years, it had been just him and me. He was an extremely giving person who enjoyed centering his life around someone he loved. What would he do when I was gone?

I needn’t have worried. The summer before I started college, he met a woman named Betty at New York’s Penn Station. It turned out they were both waiting for the train to Boston. They contrived to sit together, and before the end of the four-hour train ride, they’d started kissing. So while I packed to go to college in Ohio, Betty packed up her life in Newport Beach, California, to move in with my dad in Lawrence, Kansas. I was hugely relieved that Vati would not be alone.

The Oberlin student body was full of independent thinkers. Obies, as we called ourselves, were just as inclined to start organizations as to join them. Students taught courses and created their own majors. They took time off to travel. The message I got from my time there, perhaps more than any other, was that life is not a line, but a field. In other words: Try lots of things. Seek out varied experiences. Become a citizen of the planet. Don’t follow a predetermined path. Go out into the world and make something of your own.

The summer after my first year at Oberlin, I got my first professional acting job, at a summer stock company in Vermont called the Green Mountain Guild. About twenty other actors and I lived in a ski lodge in Killington, Vermont, with an enormous taxidermied moose head on the living room wall. Most of the actors were veterans of the New York theatre scene. At eighteen, I was the youngest in the company.

The alcoholic husband-and-wife team who ran the company was very tight-fisted. They kept a padlock on the refrigerator between meals. Our contract included room and board, and they defined that as three meals a day—not a crumb more. They policed us at mealtimes, commenting on our portion sizes and mumbling about not wanting to have to alter our costumes if we gained weight.

Despite this, they managed to attract exceptional actors. The Artistic Director was known to have an eye for talent—the young Meryl Streep had once been a part of the company. The people I worked with there were gifted, accomplished, cynical, and raucously funny. One of them—Siobhan Fallon Hogan—became a cast member on Saturday Night Live a few years later. Another—Lisa Kron—became a Broadway performer and Tony-Award-winning playwright. We called our dressing room the Killington Burn Center, thanks to the cutting one-liners my castmates tossed off with vicious speed. Most of them were five to ten years older than me, and I felt hopelessly young, naïve, and Midwestern in their presence. My face hurt from laughing, but when I was alone, I cried a lot, too.

That summer, I performed in three musicals— Sweet Charity, Evita, and The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas—and one operetta, The Merry Widow. Vati and Betty came out to see me in my biggest role, as the hard-boiled taxi dancer Nickie Pignatelli in Sweet Charity, and again as a tango dancer and ensemble member in Evita. Naturally, he thought I was wonderful and should have played the lead in every show.

I’d already considered myself a feminist when I started college, but over the course of my first year at Oberlin, I’d become much more politicized. By the end of that year, I was highly sensitized to cultural manifestations of sexism, both subtle and overt.

It’s an oversimplification to say I played some version of a prostitute in every one of the four shows that summer, but that’s how I thought of it at the time. And though I truly enjoyed the performances, my politically awakened self couldn’t escape the sense that what I was putting forward in the world was not aligned with my deepest values. Was this really what I wanted to do with my life? By the time I returned to Oberlin for my sophomore year, doubts about my theatrical vocation had begun to creep in.

MY OTHER LOVE

Fortunately, acting was not my only passion. I’d been keeping a daily journal since I was eight years old—just as long as I’d been acting. When I was nine, I’d written in those pages, “I want to be an actress and a writer on the side.” Even then, my fantasy life included not only performance, but authorship.

Stuart Friebert, the brilliant, if somewhat draconian, head of the Oberlin Creative Writing Program, did not allow students to take the introductory course until their sophomore year. As soon as I returned from my summer in Vermont, I took it and loved it.

Throughout that year, I agonized over whether to stay a theatre major, as I’d originally declared, or switch to creative writing. The choice felt monumental, as though it would determine the course of my entire life. (I had not yet internalized the line versus field concept.)

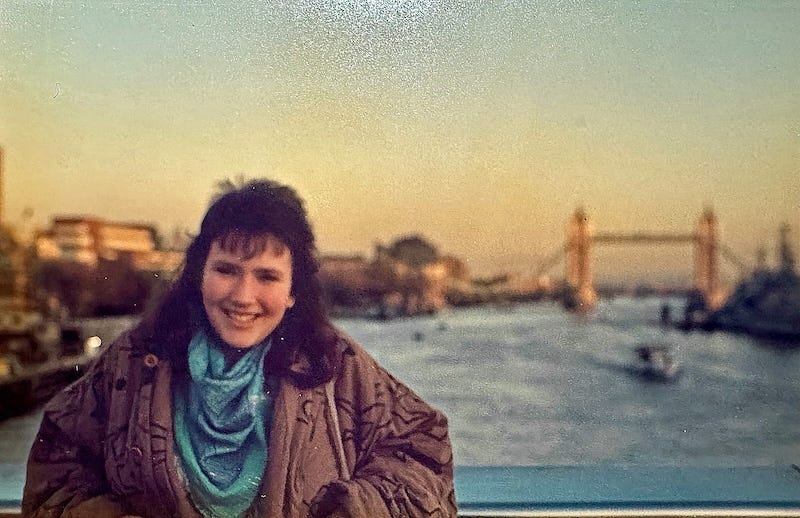

For the first semester of my junior year, I was accepted into an intensive, conservatory-style acting program with the British American Drama Academy in London. I’d be immersed in the theatrical arts for three months, taking classes in voice, movement, scene study, Shakespeare, and stage combat. I’d live in a dorm in Regent’s Park, in the heart of London, with easy access to London’s bountiful theatre scene.

I decided the semester would serve as a kind of litmus test: Either I’d return mightily inspired toward my chosen path or burned out and over it.

Ah, London. When not in class, I wandered those streets for hours, soaking in the European rain (to quote Billy Joel). I bought chunky Cadbury chocolate bars with nuts and raisins at the tube station vending machines and gained ten pounds. I got a paid gig performing in a hilarious show called Hamlet, Improvised above a pub on weekend evenings. I sang in the tube stations with some of my classmates and picked up a few extra coins.

We had classes and guest lectures with some magnificent actors, including Brian Cox (Succession) and Dame Dorothy Tutin, who’d originated roles in several Harold Pinter plays.

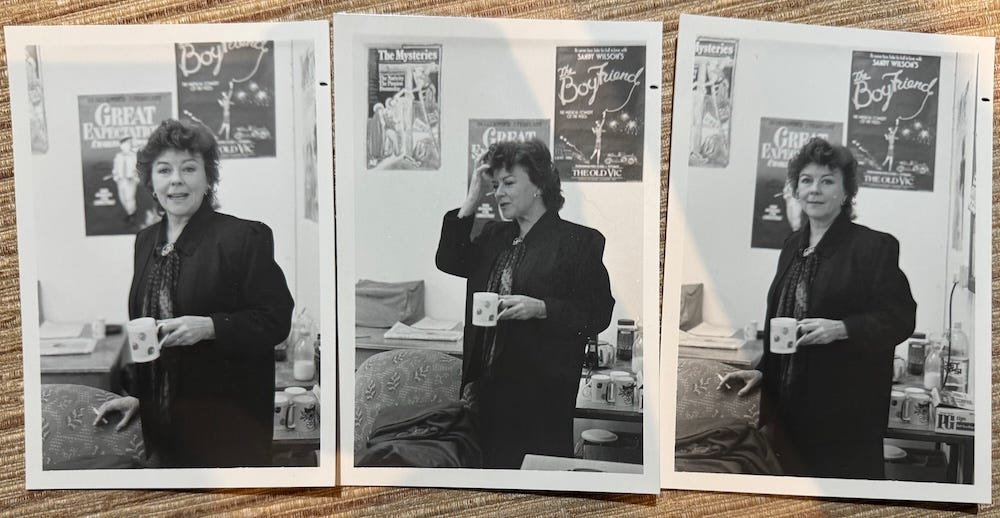

One day, an American actress came and told us the story of how she landed the role she was currently performing in the West End. I no longer remember what the role was, but I believe it was the type of character role I loved—one of those snappy, rewarding parts that come onstage and steal the show in a scene or two. She was middle-aged and stocky, with dyed red hair. She told us how, every day for more than six months, she’d dropped off her headshot and resumé at the casting director’s office, with a note asking to be considered for this role. During that time, she’d also rehearsed the entire role at home every day, in case she was called in to read. Eventually it worked, and she got an audition.

She attended multiple callbacks over several months. Then came weeks of silence. Not a squeak. Finally, she learned they’d chosen someone else. She grieved.

A year later, she got the call. Someone had dropped out. The part was hers.

This was meant to be an inspirational tale. See? Persistence pays off. My inner response, though, was, Oh, hell no. Surely I had better use for my time on earth than dropping off a headshot at the same office and running lines I might never get to perform every day for six months.

Much as I loved my time in London, my doubts about my calling remained. When I returned to Oberlin for the second half of my junior year, I changed my major from theatre to creative writing.

I worried about how my Vati would react to the news, but when I told him I was quitting acting, he wasn’t upset. He just didn’t believe me.

“Take a break!” he said. “I’m sure you’ll come back to it.”

“I’m not so sure,” I said.

“But you love it! And you’re so good at it.”

“I love other things too. Like writing.”

“So do both!”

His certainty annoyed me, but I kept it to myself.

I didn’t audition for any productions that semester. That summer, I worked on an organic vegetable farm in Maine.

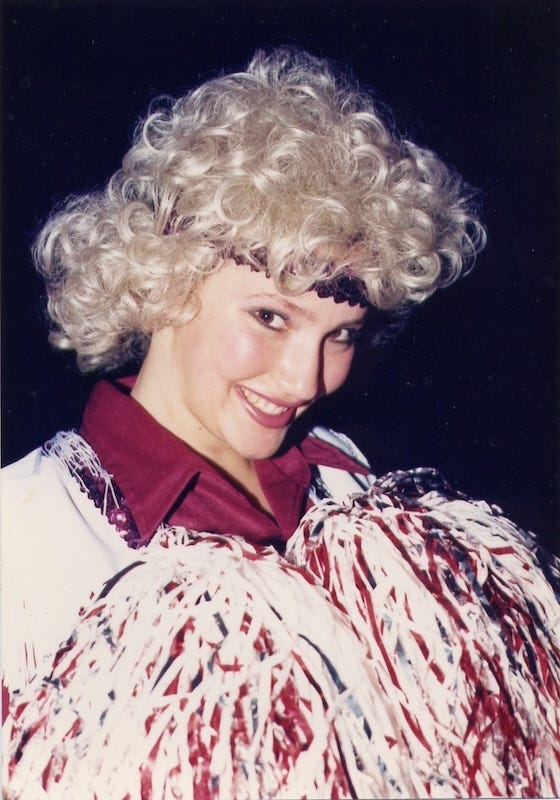

I tried to stay away from performing. Really, I did. But in my senior year, though still not auditioning, I started performing at political events. I was active in both feminist and Central American solidarity work, and I often sang at rallies. Then I started reciting poetry here and there. Next I created a two-hour feminist performance piece that incorporated music, poetry and prose—both my own writing and others’—and performed it at our campus coffeehouse, The Cat in the Cream. I don’t remember what I called the piece—I know it had a very long title—but it would later become my solo show, Miss America’s Daughters, the story of an aging beauty queen coaching her daughters on how to follow in her footsteps.

So there I was, performing again, but this time on my own terms. Saying what I wanted to say the way I wanted to say it. It felt as if I’d done it behind my own back, but I had to admit that Vati was right. I was back on stage, combining writing and performing, and it felt good.

It seemed I was learning by going where I had to go.

Stay tuned for Part 3 of You’re Gonna Be a Star Someday, coming soon to this very Substack!

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also enjoy You’re Gonna Be a Star Someday, Part 1: The Triumphant Team, about my childhood performing in Kansas; The Exuberant Professor, in which I introduce you to my beloved Vati; and Sunrise, Sunset: A Lyric Essay (about my parents’ divorce).

In other news:

Are you longing to tell your story? Four-week summer sessions of Off-Leash Writing Workshops start in two weeks! Take a deep dive into your creative process within a warm circle of supportive peers. Learn more about the process or go straight here for dates and registration.

Want to come write with me in Greece? We have four spaces left for Rejuvenate & Create: A Transformational Women’s Writing Retreat, October 5-11 on the island of Amorgos! Use code MAYMAGIC for €100 discount through end of day Friday, May 23. Learn more OR go straight here to grab your spot. A €200 deposit saves your place!

I just love this, Tanya, especially the journey from summer stock prostitutes to feminist, self-authored solo performances!

I love this so much, Tanya! Thank you for sharing these stories. It's fascinating hearing the winding paths of other multi-hyphenate creatives, not to mention inspiring and encouraging. :)