The Night I Made My Father Cry

I have only one clear memory of seeing my Vati1 cry. It happened in Florence, Italy, in August of 1982. I was fifteen.

My parents had divorced when I was nine. Since then, I’d spent the school years with my Vati in Lawrence, Kansas, and the summer and winter breaks with my mom in Berkeley, California. That summer of 1982, I’d had my first serious actor training from the Berkeley Shakespeare Festival’s Summer with Shakespeare program, where I’d gotten to work with some of the Bay Area’s best actors and directors. It was exhilarating. In addition to lapping up the training, I’d fallen in love with the other teens in the program. I felt I’d found my people. To top it all off, I had a huge crush on one of the guys.

Over the previous few years, my mom had periodically suggested that I come spend the school year with her in Berkeley.

“Wouldn’t you like to come live with me?” she’d ask, a wheedling note in her voice. Sometimes she’d accompany this with a pouty face, sticking out her lower lip.

Whenever she did this, I was overcome by a squirming, cringing kind of guilt. I’d remind myself that she was the one who’d left Kansas, my father and me behind. Still, it was terribly painful for me to say no to her. I couldn’t help imagining what it would be like to have a daughter living so far away. Putting myself in her shoes, I felt an almost unbearable sadness. I had to lash out at her in anger to rid myself of the sensation.

The discomfort of those moments was multifaceted. The truth was, I would have loved to live in Berkeley. Even before my Summer with Shakespeare, I considered Berkeley a kind of mecca for nonconformists, a place I could be wholly myself. Whenever I visited, one of the first things I’d do was stroll up and down Telegraph Avenue, where artisan stands lined the sidewalks leading up to the university. I was entranced by the handmade jewelry, the spinning crystals casting out rainbows and the bright tie-dyed garments laid out in the California sun. I was equally taken with all the wild-looking characters hanging around, from the Bubble Lady to the Naked Guy. They all seemed to my Midwestern teenage self to be utterly free, living life on their own terms.

The guilt I felt when I considered my mom’s feelings, however, was nothing compared with the anguish that consumed me when I imagined leaving behind my Vati, the sweetest man on earth. We were a team. How many times had I heard him tell people that his life’s greatest joy was raising me? He’d been through so much suffering in his life already. How could I deprive him of his greatest joy? Besides, he needed me.

For as long as I could remember, I’d worried about my father’s health. He was forty-seven years old when I was born, nearly twice the age of most of my friends’ parents. His asthma frequently rendered him out of breath and fumbling for his inhaler, and his chronic bronchitis often produced violent fits of coughing. There was also a parade of surgeries: hernia, prostate, and the endlessly returning vocal cord nodes he called papillomas, which he’d gotten removed more than a dozen times. I’d gotten used to camping out at friends’ houses while my dad was in the hospital. I’d been keeping a diary since I was eight. Each day’s entry ended with a prayer for his health: “Please let Vati be okay, please let him live a very long infinity long time, please please please please please.”

On that August night in 1982, after spending most of the summer with my mom, I’d flown to Florence with my Vati for a two-week vacation before the start of my junior year of high school. Shortly before I left, my mom had once again tried to coax me into living with her. Just say the word, she said, and she’d enroll me at Berkeley High. I could continue my acting training and hang out with my new friends. I could see that boy I liked so much. I’d yelled at her to leave me alone, but I was torn.

On the flight to Italy, I couldn’t stop thinking about my mom’s offer. My dad knew, of course. We were best friends; nothing stayed hidden between us. And though he told me I should do whatever my heart desired, I wasn’t fooled. I could see the effort it took for him to shape those words.

When we arrived in Florence, we rented a car, and my Vati drove us to our pensione, a cross between a hotel and a bed and breakfast. Pensiones at that time usually had between eight and twenty rooms, individually furnished with heavy, old-fashioned wooden furniture. They always had fat white duvets on the beds, folded into crisp, puffy envelopes.

We got our key—one of those satisfyingly thick old-fashioned ones that jangles around in a keyhole wide enough to peer through—and brought our suitcases up to the room. Vati’s bag was heavy, filled with his medications. His history of hernias prevented him carrying heavy objects, so either I lugged our bags up the stairs or we took the help of a porter, if the pensione was large enough to have one. In any case, we got the suitcases upstairs, and Vati went to go park the car, which we’d left double-parked at the curb.

I flopped down on the bed, took out my journal and began to write about the journey.

After a while, I became aware that the sky outside my window, which had been dusky when we arrived, was now completely dark. How long had it been? I looked at my watch. More than half an hour had passed. Where was Vati?

I waited a while longer, then went downstairs and told the person at the desk—a painfully thin woman with dyed black hair and bright red lipstick—that my dad had gone to park the car and hadn’t returned. It had been close to an hour at this point. Her English was not great, and my Italian was non-existent, so communication was challenging.

When I’d finally made myself understood, she said, “Parking difficult this area. He come soon.”

I went back upstairs.

There were no cell phones then, only pay phones. As time passed, I ran up and down the stairs between our room and the lobby multiple times, asking whether he’d called. Finally, panicked, I asked her to call the police.

“Police?” she said skeptically, “no need.”

“Yes, need!” I said. “It’s been an hour and a half! He might be hurt! I have to find him!”

“We wait little more. If not come, we call.”

“How much more?” I started to cry.

“Little.”

I went back up to my room and threw myself once more onto the bed, sobbing. My heart pounded. What if he’d been in an accident? What if he were dead?

I whispered the prayer I’d written so many times in my journal, “Please let Vati be okay. I’ll be good, I’ll do whatever you want, please oh please oh please please please.”

As I did this, a part of me flew out of myself and up to the ceiling. It hovered there, looking down on my weeping self in judgment.

This is unhealthy, this part scolded. You’re just a kid. You shouldn’t be spending so much time worrying about your dad. He’s supposed to be the parent!

This critical self reminded me of all the times I’d played an adult in my relationship with my dad, from chatting with him about girlfriend woes to talking him down from panic attacks. A flash of anger rose up alongside my fear.

If he comes back alive and well, you should take your mom up on her invitation and go live with her, this other self said. You need to separate yourself from this overdependence you and your dad have on each other. It’s too damn much.

Two hours had passed. I’d cried myself dry. I was just about to go downstairs and demand the woman call the police, when the door opened and in walked my Vati, red-faced and out of breath. He sat down heavily on the bed.

“What happened?!” I yelled. “Where were you?”

“I got lost,” he said. “I had to go a long way to find a parking place. I walked and walked. The streets all look the same. And I couldn’t remember the name of the pensione! Finally, I asked a police officer for help. He drove me around in his car until I found it.”

“I was so worried,” I said. “I didn’t know what to do.”

“I know. I’m sorry. I was frantic too, worrying about you!”

All the emotion of the last two hours welled up in me.

I steadied my voice. “I’ve made up my mind,” I told him. “I’m going to live with Mom next year.”

“What?” he said. His voice, roughened by so many surgeries, came out a high-pitched squeak. “Why?”

“We’re too dependent on each other!” I yelled, everything flaring back up. “It’s not healthy!”

My Vati turned away and put his face in his hands. His back shook with poorly suppressed sobs. It wasn’t enough he’d spent the last two hours frantically searching for the hotel. Now he would lose me too.

Looking back on that moment, I’m appalled by the cruelty of my teenage self. Could I possibly have chosen a worse moment to speak those words to my dad? At the same time, I feel a deep compassion for that girl, self-absorbed though she was. To her, the choice of where to spend her last two years of high school felt unbearable. Whatever she did would let down one of her parents. Whatever she did would let down a part of herself.

I ask myself, too, whether the judgy voice that emerged that night was right. Were my dad and I overly enmeshed? Sure, in an ideal world, I would have spent less time worrying about my father’s welfare. In an ideal world, he would have enjoyed perfect health. In that world, there would have been no Hitler, and he would not have lost his home, his country and his planned career. He would not then, in his new life in the US, have gone on to lose his first wife, second child, mother, grandmother... In that perfect world, he could have stayed in Austria. Then again, in that world, my parents would probably never have met, and I would never have been born.

Obviously, we don’t live in that world. In the broken world we inhabit, I was blessed with the most loving, devoted father a girl could ever want. And honestly, where did we get the idea that parents should be invulnerable and young people carefree? Speaking as a flawed, sometimes emotionally overwrought parent myself, I think perhaps it’s time to give that idea a rest.

Our imperfect lives make us who we are. On good days, I like the person I am. Much of that is thanks to my dad.

Ultimately, I did not go and live with my mom. I finished high school in my hometown, allowing my dad to exult in the fact that he’d raised me until I was ready to leave the nest. Then, although my dad murmured about the University of Kansas and my mom suggested I apply to UC Berkeley, I set my sights on Oberlin, Ohio, and I was gone.

If you enjoyed this story, you might also enjoy these other memoir pieces: The Exuberant Professor; Sunrise, Sunset: A Lyric Essay; The Road Between Us: A Daughter’s Story; On Forgiveness.

Itching to write your own memoir? I lead writing workshops and retreats to help free your voice and craft your story. I also offer private coaching and editing services. Visit my website to learn more and get on my email list to be notified of future opportunities.

Pronounced FAH-tee: German for Daddy

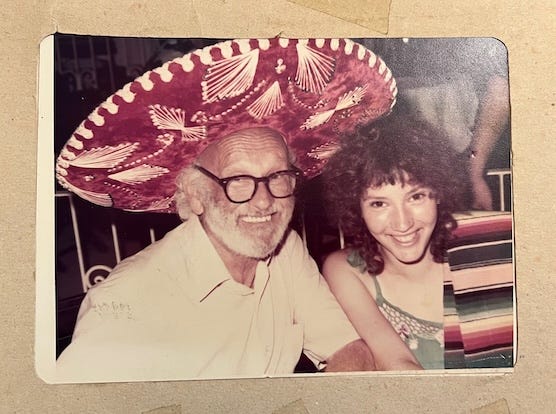

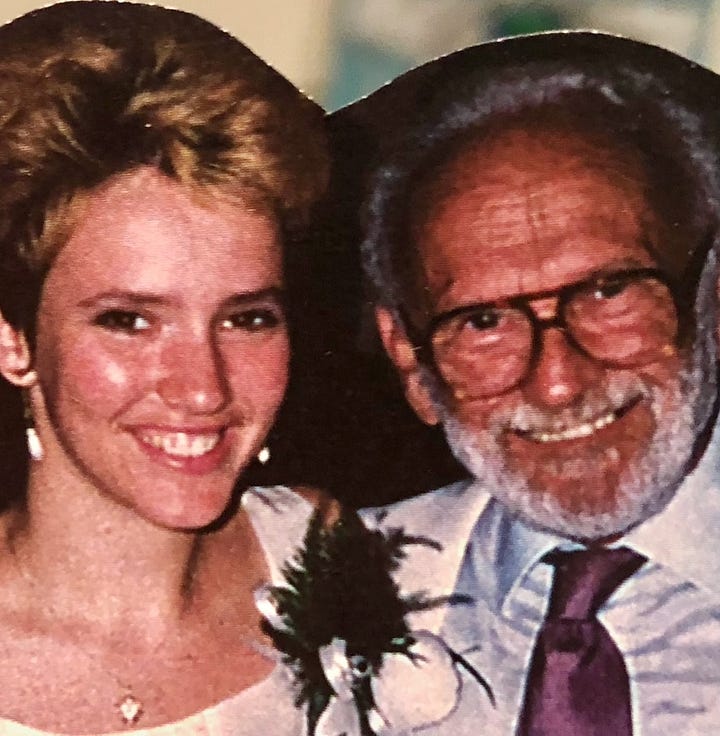

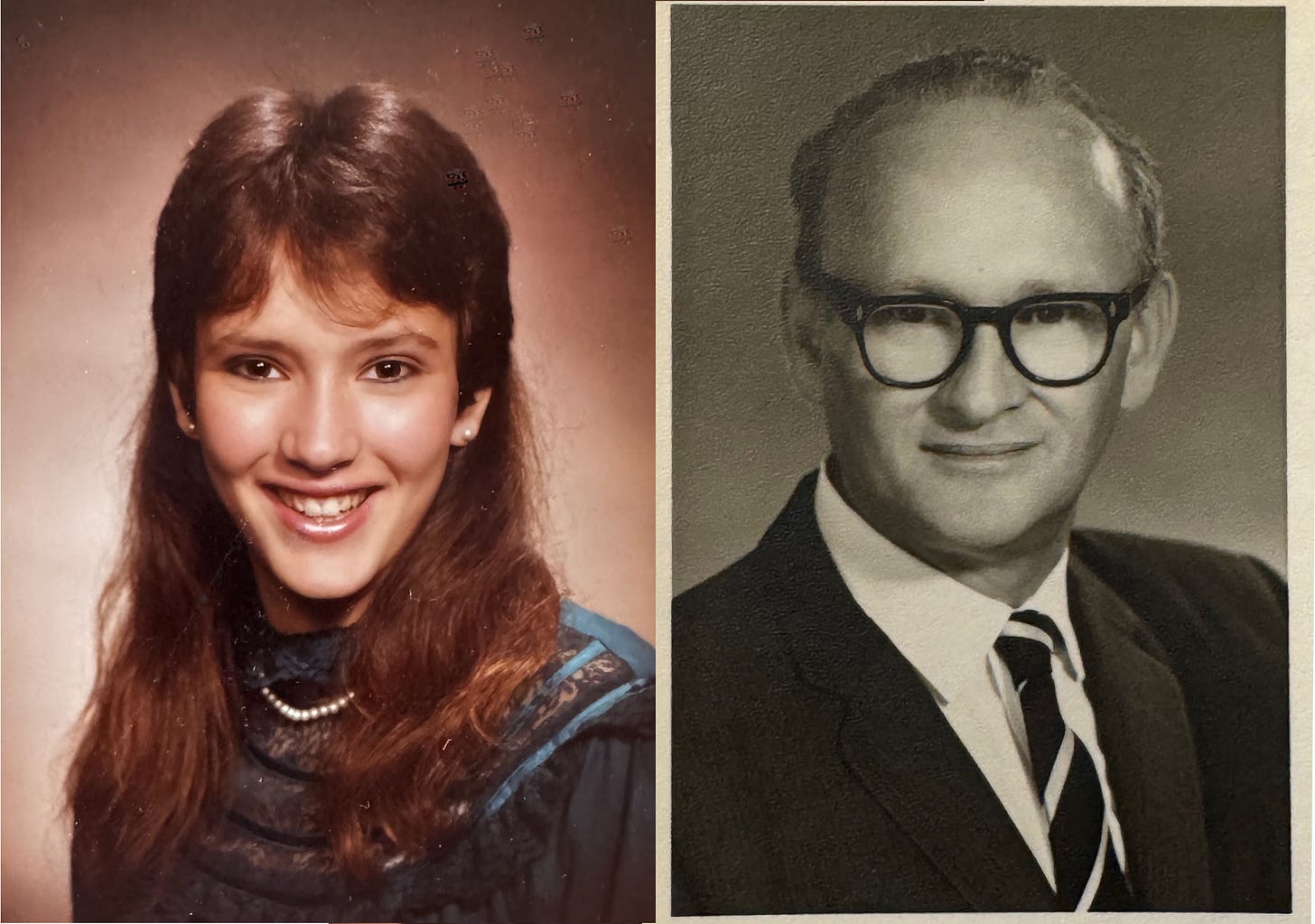

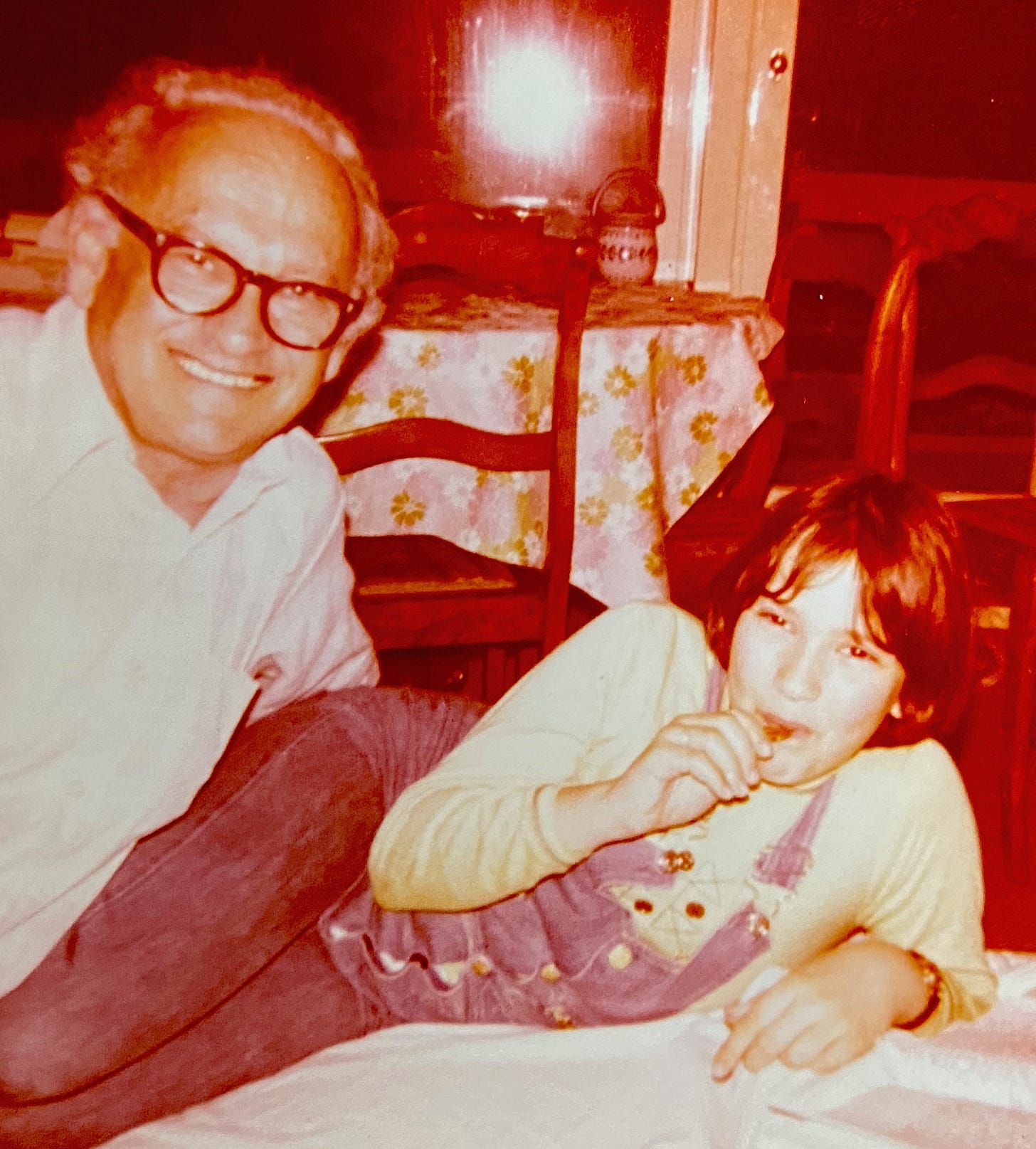

You have such a beautiful, clear narrative style. It brings every scene and character to life. And I was charmed by the pictures of you through your storied life. You've been remarkably lucky to have so much love and support from your family - what a fascinating, complex intersection of personalities.

Tanya, I'm so grateful you shared this story. What a wrought day for both you and your dad.

I'll never forget the beautiful energy he held as a 4th grader listening to him share at Broken Arrow elementary, in the music room. Then years later, sitting in his lecture hall at KU. I enjoy your writing so much.