After Ada Limón

“Before the road between us, there was the road beneath us.”

-Ada Limón, Before

Before there was California, there was Kansas.

Before the house on Parnassus Road, there was the house on Jasu Drive.

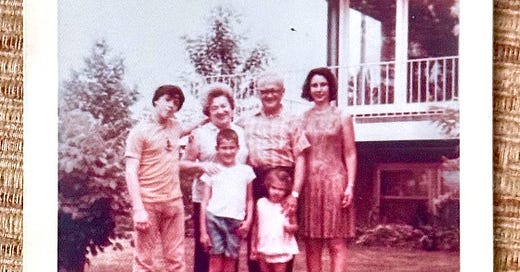

There was my middle brother Ron-Ron, nine years my senior, protecting me from the torments of Lennie, who was four years older than me. I was the baby.

There was my oldest brother Bernie, nineteen when I was born, coming and going in overalls with no shirt underneath, smelling of cigarettes and hay.

There was pretty Mommy in her blue nylon nightgown, coming to kiss me goodnight. Her pale face and dark hair, the cool scent of Noczema. Her high sweet voice singing allllll the pretty little horses.

There was Shhhh, Mommy’s working.

And always, always, there was Vati, my Austrian-born Daddy, his scratchy voice and warm hands; his safe, comforting lap.

Before the road between us…

Mommy! Mommy! I yell at the top of my lungs. I’m three years old, lying in my bed.

Vati comes in.

Can I help? Mommy’s downstairs working.

I want Mommy.

Vati goes out and comes back with Ron-Ron.

Can Ronnie help?

No! Mommy.

Vati and Ron-Ron go out and come back with Lennie.

Can Lennie help?

Mommy.

Finally, Vati goes to the basement study, gets Mommy, and brings her to my room. He and my brothers stand behind her in the doorway.

We all want to hear what was so important, someone says.

Mommy, I say softly, Do you love me?

Before the road between us…

My mom, Juliet, was a twenty-eight-year-old Associate Professor of Psychology when she met Harry, my dad. Born Hans Georg Schaffer, he’d changed his name when he arrived in this country during World War II. He wanted to remove all traces of Germanness from his name.

Harry was raising two sons on his own: Bernie and Ronnie, a teenager and a toddler. Both boys had lost their mothers early in life—one to death, one to mental illness. Both mothers were Holocaust refugees like Harry.

When Juliet agreed to marry Harry and become a co-parent to his two boys, she thought, I like children. This should be no problem.

Ronnie’s mother relinquished custody, and Juliet adopted him. Lennie and I came later.

There was the road beneath us.

Before the flights across the country, Kansas to California and back, there was the drive across the country in Red Pete, our VW van.

There was Vati, Mommy, Lennie, and me singing The Shaffer Family to the tune of The Addams Family. Bernie stayed behind in Kansas. Ronnie, fifteen, was somewhere in San Francisco, adrift in a sea of itinerant youth. That story—a mother’s rejection; a father’s capitulation; a long-haired, unwashed, pot-smoking teenager in desperate need of love—left a gaping wound in the heart of my family that I knew nothing about at the time.

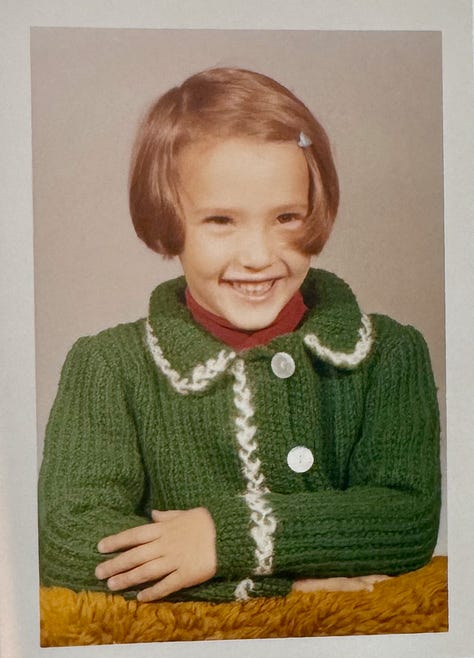

It was 1973. I was six years old.

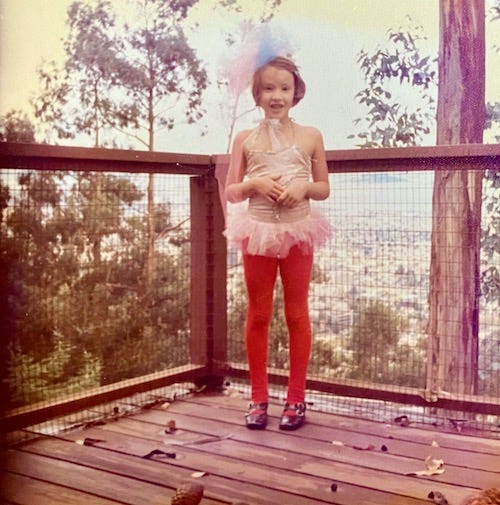

There was California here I come. There was Open up that Golden Gate.

There was car camping. There was my asthmatic, academic, not particularly handy Vati proudly pitching a tent—I helped!—and lighting a gas stove. Lennie and I gathered sticks for the fire. Vati taught me to make an A out of logs, then add kindling and newspaper underneath. Where was Mommy? I don’t see her in this picture. Maybe sitting in Red Pete with her book.

At a playground in California, my parents abruptly stopped talking when I ran up to them. Months before they broke the news to Lennie and me, I thought with perfect clarity, They’re going to get a divorce.

So much breaks in a family, in a life, in the life of a family.

Four Shaffers drove to California in 1973, my parents on sabbatical from their teaching jobs at the University of Kansas. We stayed in a house on Parnassus Road, high in the Berkeley Hills. My dad taught at UC Davis, commuting a few days a week. My mom did post-doctoral work in statistics at UC Berkeley with the prominent statistician Erich Lehmann, with whom she fell madly in love.

Two families came apart in the wake of that passion, that love story between two reserved, soft-spoken intellectuals who occasionally stayed up into the wee hours discussing math problems. Lovers of classical music—“serious” music, Erich called it—readers of scientific journals and, in his case, German literature. Erich, a Holocaust refugee like my father, would never return to Germany, but he loved the music, the poetry, the novels…all the old German masters.

The road between us

You were a leaver, Mom.

You left your first husband, whom you’d married fresh out of college. He reportedly never got over you.

You left my Vati. He eventually got over you, but it took ten years.

You left me. Did I get over you?

You didn’t leave me as completely as Bernie’s and Ron’s mothers left them. You called every Sunday. You visited every month or so. And I spent winter and summer breaks with you.

And yet, to a child…

When I was little, Vati called me Mommy Girl, because I always asked for Mommy. He didn’t mind. It pleased him to see how much I loved you. He loved you that much too.

After the divorce, my loyalties shifted. I became a Daddy Girl and stayed that way for many years. When I was a teenager, every word you said felt like sandpaper against my skin.

It seemed the feeling was mutual. When I visited, you were always shushing me, wincing and pointing to your ears. Nothing drove me crazier. The more you shushed, the louder I yelled. The slam of my bedroom door rocked you and Erich’s small apartment like a minor earthquake.

In the early nineties, when I was volunteering in Ghana, I called you from a telephone office in Accra. You asked if I needed anything. I said I could use a new flashlight.

A few weeks later, a package arrived: a slim, lightweight flashlight and extra batteries. You’d clearly researched the best product for a young woman carrying her life on her back.

Sometimes when I think of you, I think of that flashlight, its strong beam. We all show love in the ways we can.

You and my stepfather Erich were perfectly matched. You stayed together thirty-five years, until his death at ninety-two—the same age you are now. To this day, you describe those years as heaven.

You were born in 1932. Your mother wanted you to pursue music; you chose math. Quiet as you were, again and again you took steps toward your own happiness that were virtually unheard of for a woman of your time.

You modeled that for me. Should I thank you for it?

In your eighties, you married your fourth husband, George, a man five years your junior.

After you and George attended The Fourth Messenger, the musical I wrote with composer Vienna Teng, George sent me an email.

It’s clear this musical is about your mother, he wrote.

I told him he was wrong. The musical was based on the legend of the Buddha, who abandoned his wife and infant child to pursue enlightenment.

Still, he may have had a point.

A few years later, George died. My Vati and your first husband were both gone by then as well. Your mother, my Grandma Harriet, had outlived three husbands. You outlived four, though of course you’d left two of them long before.

The road beneath us

You were a leaver, Mom, but that hardly matters now. You are no longer you. Or rather, you are you, but the you of today is not the you of my childhood. You are pure sweetness now. All your prickly parts—the anxious, rigid, critical parts—are gone.

One day about ten years ago, we’d arranged to meet for lunch at a café in Berkeley. I arrived a few minutes late. You weren’t there.

I waited a few more minutes, then called.

You’d gotten caught up in work and lost track of time. You’d leave right now, you said. You were just fifteen minutes away.

That had never happened before. Not once in my entire life had you been so much as a minute late.

We had a lovely lunch that day. I remember thinking it was the most intimate conversation we’d ever had. We talked about your college boyfriends, about heartbreaks. Things you’d never been willing to share. I learned that you left your first husband because you were bored.

Looking back, I see these two things were connected—your losing track of time and the unguarded conversation we had that day. It was the beginning of a softening taking place in your brain. A softening that made it possible for my brother Ron to forgive the anguished history between you. The person who hurt him is no longer there.

Now the details of your life come and go. Sometimes you remember the people and events of your life; sometimes you don’t. The person you are is untroubled by this. The person you were would have hated it. That person—private and fiercely independent—would have hated “assisted living,” with people coming in and out all the time, asking How are we today? in extra-loud voices, taking your temperature, handing you little cups of pills and watching you swallow them. As if you were helpless. As if you were old.

But this person, the one you are now, is as easygoing as they come. If I ask you, What did you have for lunch?, you shrug and say, with a little laugh, I don’t remember!

You recognize me, your daughter. Your face lights up with a radiant smile when I walk into your room or appear on the screen of your phone. You say, I love you, with warmth and tenderness every time we say goodbye.

The road before us

We sit on your couch doing a jigsaw puzzle with about forty large pieces. Your hands move slowly, as if underwater. You were top of your graduate class at Stanford. Now you hold a puzzle piece with knobs and sockets on all four sides and try to fit it into a corner spot. When you set it down, I gently place the corner piece in your hand.

You sit with a book open in your lap, gazing at the page. If I ask what it’s about, you read me the first sentence.

You will never read this essay. And your next act of leaving, when it comes, will not be by choice.

Please know, before you go, that between us all is forgiven.

Time has sanded away my spiky parts too.

Only love remains.

This story is part of an ongoing memoir project that’s coming to me like a puzzle, in bits and pieces. If you enjoyed it, you might also enjoy Sunrise, Sunset: A Lyric Essay, which reflects on my parents’ marriage and my own, and The Exuberant Professor, about my remarkable dad.

And yes, the eyes, cheeks, and smile are a dominant gene!! Stunning to see all three of you “together” ❤️

So touching and powerful, Tanya. Gorgeous essay. Here’s to the sweetness you’ve found.