Friends!

Before I share with you this story of a magical encounter in my life, I want to let you know that in July I’ll be offering three FREE Comfort-in-Community Off-Leash Writing Sessions. These online offerings are free and open to all who would like to participate. I’ll provide prompts and guidance, and we’ll write together in real time. If the group is large, we’ll divide into breakout rooms to share our writing. Learn more and register HERE.

Today’s offering, My Fairy God-Juggler and Beyond, is the third part in a series called You’re Gonna Be a Star Someday, about how much my Vati (pronounced FAH-tee, German for Daddy) loved seeing me perform on the stage, and how we both believed I was destined for stardom. It follows Part 1 (The Triumphant Team) and Part 2 (Where I Have to Go), but it is also a self contained work that can be fully understood and enjoyed on its own.

I dearly wish that this multi-part story—itself a part of a larger memoir-in-progress about growing up with my remarkable Vati—will resonate with your own life experience in meaningful ways.

Warmly,

Tanya

My Fairy God-Juggler and Beyond

Sometimes the right person shows up at precisely the right time.

As graduation from Oberlin College loomed, I entertained wildly varied notions of what to do next. All around me, people were applying to grad schools, jobs and internships. One friend was going off to teach English in China. Some theatre pals were heading to New York, LA, or Chicago to try their luck on the professional stage.

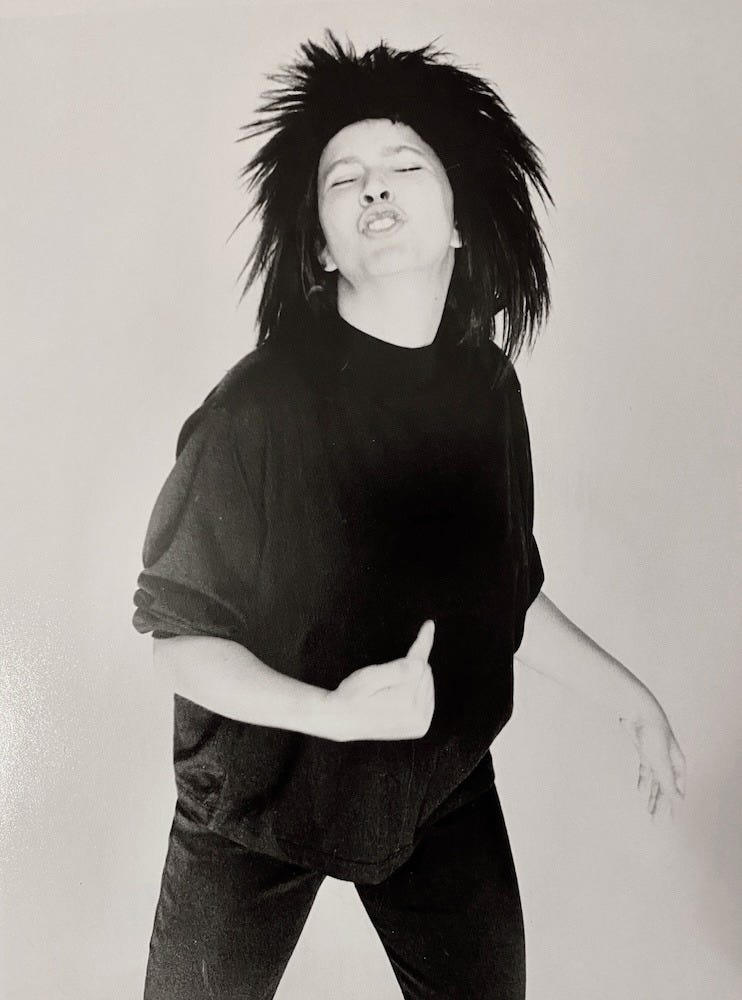

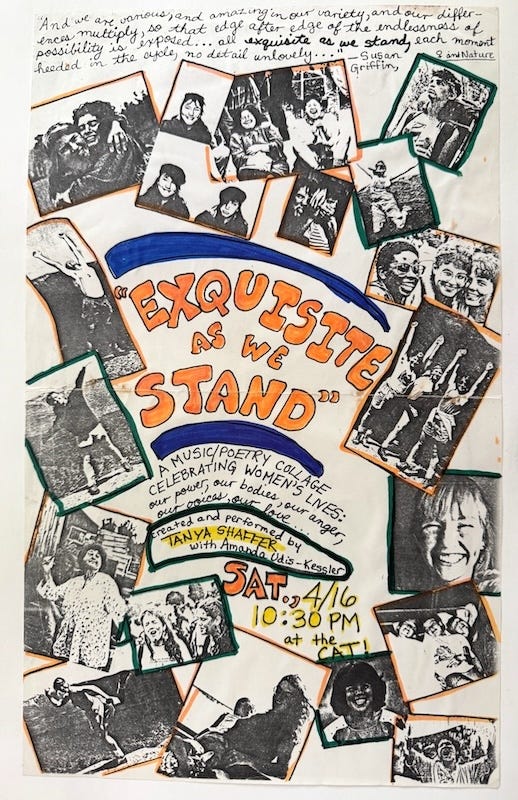

When I thought deeply about it, I realized that what excited me most at that moment was performing the cabaret-style show I’d developed with my songwriter-pianist friend Amanda Udis-Kessler. We’d been doing it semi-regularly at Oberlin’s Cat in the Cream Coffee House, with various titles. The show was a loose collection of poems, monologues, and songs, by myself, Amanda and others, about women’s body image and cultural expectations of what it meant to be female.

If I could keep doing this, I would, I thought, but how could I?

On a beautiful spring day shortly before graduation, I was walking barefoot across the big grassy field in front of the library, turning these questions over and over in my mind, when I spotted a man I’d seen juggling on the sidewalk earlier that day. He was lying back in the grass with his hands behind his head, gazing up at the clouds. He had an artsy, middle-aged hippie vibe and a gnome-like quality of mischief and wisdom. I said hi, and he invited me to sit and chat. He asked what was on my mind, and I poured out my predicament. I told him I’d love to travel around the country performing my show, but I had no clue how to make that happen.

“No problem,” he said cheerfully. “I can tell you how to do that.”

It turned out he was a professional street performer. The college had hired him that weekend to entertain the groups of alumni and prospective students who were roaming around.

We sat in the grass for the next hour, while he talked me through the basics of booking a tour.

“First, get some good photos taken,” he said. “Ask folks who’ve seen your work—preferably folks in the business—to give you quotes about how fabulous you are. Print up a brochure—printed, not photocopied, that’s important—and Voila! You’ve got booking materials.”

I must have looked stunned, because he looked me in the eye and said, “You are whoever you say you are.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that if you call someone up and tell them you’re a touring performer, that’s exactly who they’ll think you are. And they’ll be right to believe it, because that’s who you’ll be.”

Colleges, he told me, were always looking for interesting acts to fill their calendars.

“They’ve got money for it!” he enthused. “It helps to have an angle. What’s the show about?”

I described the show as best I could.

“Perfect!” he said. “You can connect with women’s centers, women’s studies departments, things like that.”

“Just remember,” he continued, “you can ask anybody anything.” To this day, I invoke those words whenever my courage threatens to fail me.

“Nice chatting with you,” he said. And then, as if in a children’s tale, my fairy god-juggler ambled off into the bright spring day. I never saw him again.

I came away from that hour determined to take my show on the road.

I went back to my shared off-campus house and called a woman named Judy in Oakland, California. Judy worked for my idol, the activist singer-songwriter Holly Near. I’d talked a lot with Judy earlier in the year when the Women’s Center produced a Holly Near concert on campus. Buoyed up by the words you can ask anybody anything, I asked Judy’s advice on booking a tour for myself. She promptly invited me to come to the San Francisco Bay Area and become a paid intern at Holly’s company, Redwood Records. I’d learn about every aspect of tour coordination and promotion.

The Bay Area was already my second home. My mom lived in Berkeley, and I’d spent summer and winter breaks visiting her there since I was nine. All three of my brothers were now living there too. I accepted the position on the spot. Finally, I had a plan. I was now two for two on connecting with the right person at the right time.

When I told Vati about my new position, he was ecstatic. He marveled that I’d gone from listening to Holly Near’s records to working for her. And I’d learn to book my show! I’d go on tour, fulfilling the dream of writing and acting both, just as he’d said I could. He promised that as soon as I was ready to take it on tour, he’d help set up a gig in my hometown of Lawrence, Kansas.

In the expansive hours I spent driving Stacy, my red Buick station wagon, across the country from Ohio to California, a narrative structure for my show began to take shape in my mind. One of the poems I’d been performing was called Miss America Comes Across Her Daughter, by Pamela White Hadas. In this poem, a narrator, whom I always pictured as an aging pageant queen, coaches her daughter on how to walk, talk, smile, and behave. The poem begins:

There you are at the three-way mirror, the same

mirror I grew up in, checking left and right

profiles against each other…

As the poem progresses, it becomes clear that the daughter is not responding well to her mother’s direction—she’s inept, recalcitrant, or both. As the mother’s frustration builds, her tone becomes increasingly frustrated, even unhinged.

It struck me that this poem, divided into sections, was the perfect frame for the show. I’d intersperse scenes of the beleaguered mother with scenes of a variety of daughters, each resisting her mother’s instructions in her own way. As soon as I had the shape for the piece, a title popped into my mind as well: Miss America’s Daughters.

Amanda had initially planned to move to the Bay Area too so that we could continue working together, but ultimately decided to stay closer to her own family on the East Coast. We parted ways amicably, with mutual wishes for each other’s continued creative journeys.

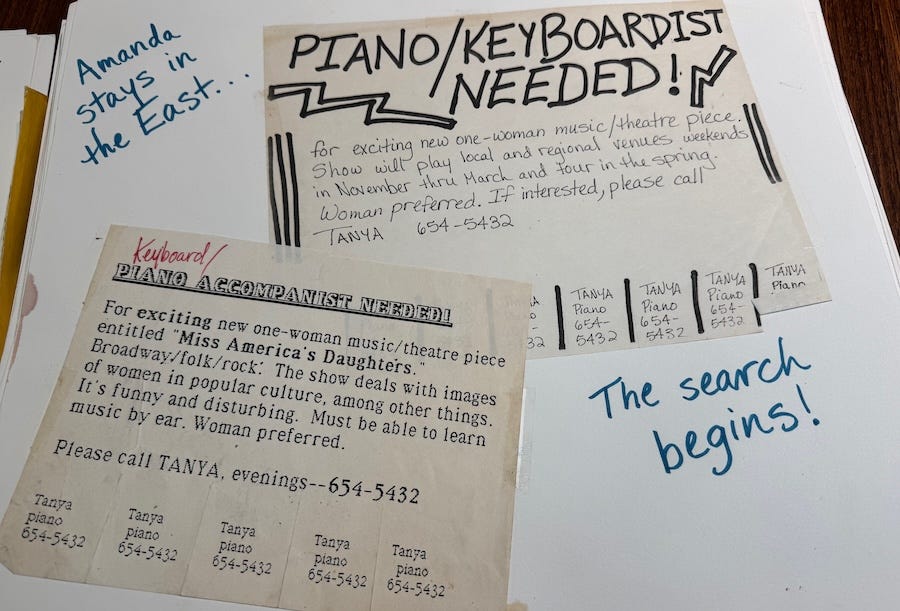

In the Bay Area, I put up signs and soon connected with a young woman who went by the mononym LauraMichele. Within six months, we began performing around town.

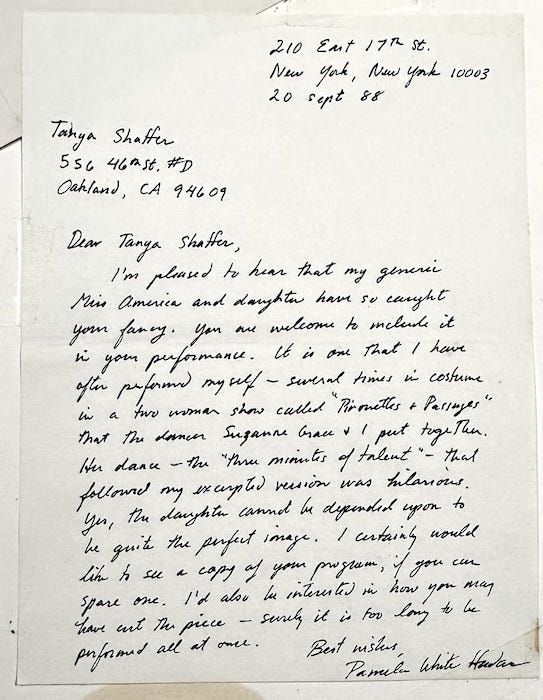

I hadn’t previously sought permission from the various artists whose work I was using, but I did so now. The handwritten response from Pamela White Hadas, author of Miss America Comes Across Her Daughter, remains a cherished artifact.

As soon as I could swing it, I took the juggler’s advice and created a brochure, including quotes from my bosses at Redwood, who’d come out to support my early efforts.

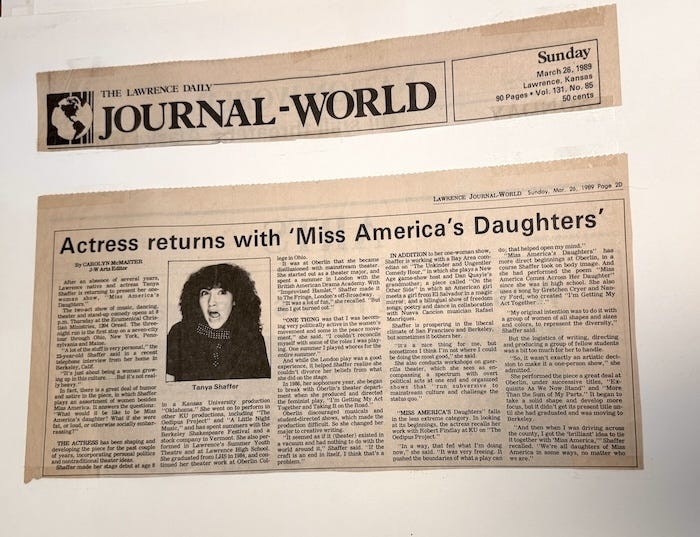

Redwood was a flexible and supportive employer and allowed me to take time off for out-of-town gigs. For the next year and a half, I performed Miss America’s Daughters in all sorts of venues—colleges, cafés, school auditoriums—even, occasionally, an actual theatre.

It was a happy time for me. Creating, promoting and performing Miss America’s Daughters felt like a perfect alignment of my values and abilities. Some audiences were big, some tiny—I didn’t care. I was doing what I loved. Returning to Oberlin to perform, sponsored, of course, by the Women’s Center, was a highlight.

Vati made good on his promise to book me in Lawrence. He called contacts at the Journal World and the Daily Kansan and made sure I got plenty of press coverage. The house was packed with friends who’d known me since childhood. His smile could not have been brighter as we both reveled in the after-show accolades. I really did feel like a star that day.

But Vati had raised me to be an activist as well as a star. In the mid-80s, when I was in college, the hot-button issues on campus were apartheid in South Africa and CIA-sponsored wars in Nicaragua and El Salvador. At Oberlin, in addition to working on women’s issues, I’d become deeply involved in the Central America solidarity movement. I continued this activism after graduating college in 1988.

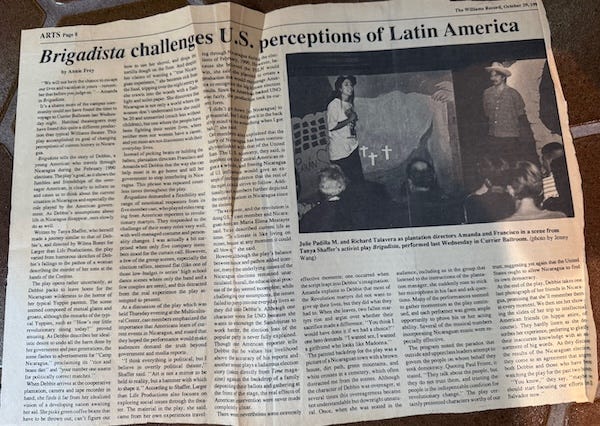

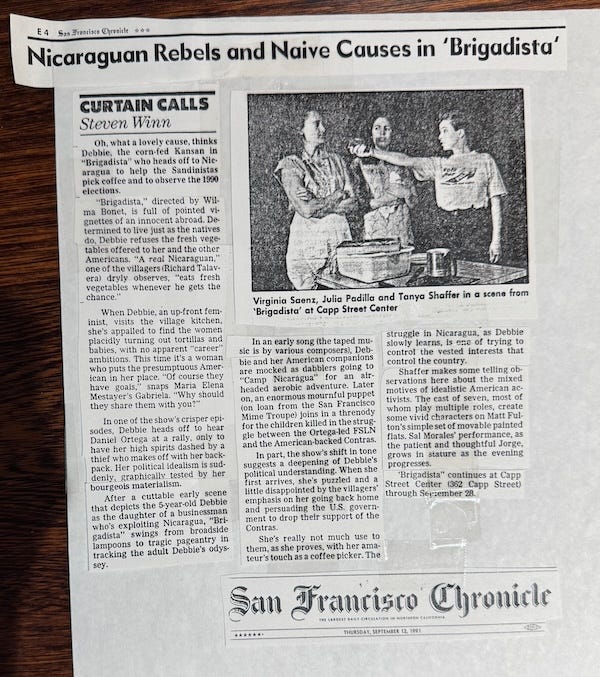

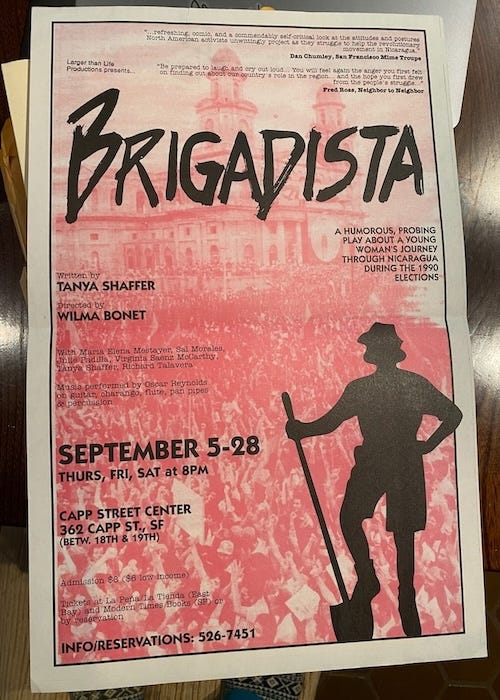

In 1990, I traveled to Nicaragua, where I picked coffee, attended a peace march, and became an official election observer. When I returned to the Bay Area, I started work on a new performance based on my experiences there. I thought it would be another solo piece, but it quickly morphed into a multi-actor play called Brigadista. In 1991, I produced and acted in Brigadista in San Francisco, directed by Wilma Bonet. We followed it up with a 21-city tour for eight actors, a tech person, and a political organizer, who came along to network and strategize with Nicaragua solidarity groups around the country.

How did I have the nerve to coordinate a 21-city-tour cross-country tour for ten people at the age of twenty-four?

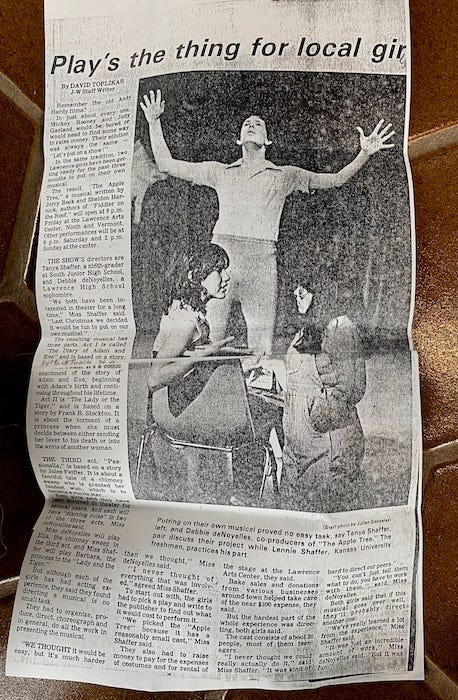

I’ll answer that by whisking you back in time to 1979, when I was in seventh grade. I saw a musical called The Apple Tree, by Jerome Bock and Sheldon Harnick, and loved it. The Apple Tree is divided into three acts, each of which tells a separate story. I particularly loved the second act, The Lady and the Tiger, in which a princess is caught with her low-status lover and must choose whether to send him to his death or into the arms of another woman. I desperately wanted to play the princess.

Since no one nearby was producing The Apple Tree and inviting me to audition, Vati, whose perennial attitude towards any challenge was, Why not?, suggested I produce it myself. My best friend Debbie and I decided to do it together. I’d play the princess, she’d play the female lead in Act 3, and we’d fill in the other roles with our friends and family.

With Vati’s guidance and supervision, Debbie and I went to the library to track down the address of the company who licensed the script. We sent a typed inquiry by mail and obtained the rights to produce the show at the lowest amateur rate. We then called around to local businesses soliciting donations to rent the Lawrence Arts Center for two performances. I still remember how surprised I was when the owner of Karpet King said yes to my stammering appeal and agreed to donate ten dollars. My first fundraising success! We posted xeroxed flyers around town and managed to half-fill the house for two performances. We even came out a few dollars ahead. I guess in that instance, as with so many others in my life, Vati was the right person at the right time to help me transform daydream into reality. (And you better believe he helped us get press for that one, too!)

I learned through that experience that any large project can be broken down into manageable steps. So when it came to taking ten people on a national tour, I approached it the same way. After all, how hard could it be?

With Miss America’s Daughters, I’d gotten used to booking tours for myself and a very chill musician named Ed Roseman, who’d replaced LauraMichele as my accompanist. The guiding principle was financial solvency. This involved securing as many gigs as possible, staying with community hosts, and taking the cheapest mode of transportation available. It never occurred to me that I should consider other factors when organizing travel for ten people, some considerably older than me.

I’d warned every actor who auditioned for Brigadista that community housing might mean crashing in sleeping bags on people’s floors. They all said that sounded like a lot of fun. I didn’t know yet then that actors will say anything to get the job.

The ten of us crammed into a borrowed van, with the set strapped to the roof, and traversed the country from California to Massachusetts, performing in twenty-one venues in two months. This sometimes meant unloading and erecting the set, running lighting and sound cues in the performance space, doing the show, taking down the set, hoisting it back onto the van, and driving onward towards our next destination, all within the course of a single day.

Our company of ten inspired creative souls putting on a show with a meaningful message soon devolved into nine exhausted, pissed-off individuals united in their hatred of the heinous fool who’d created this untenable schedule.

The low point of the tour came when a community group in Baltimore housed us in a soon-to-be homeless shelter: a cold cement-floored basement filled with cots in a sketchy neighborhood. Two actors decided they’d had it and left without notice. The political organizer stepped into one of the parts, and we discovered that, by reshuffling some roles and gender-flipping others, the piece could be done with seven actors instead of eight. Then another actor, upset that her role had not been sufficiently expanded in the reshuffling, decided to leave as well, though she, at least, had the courtesy to give a week’s notice. I cracked open the piggy bank and flew out another Bay Area actor to replace her, who learned her parts in record time (Thanks for saving our asses, Tessa Koning-Martinez. All these years later, you still have my gratitude.)

There were times during those two months I thought I’d implode from stress. Even the sight of Vati’s beaming face when we played in Lawrence was not enough to lift my spirits. Yet somehow, despite every obstacle, we made it. We never canceled a show. Audiences loved us and frequently rewarded us with standing ovations. I guess you could call that a win.

This stark encounter with everything I did not know about managing my fellow humans left me shellshocked and drained. The desire to leave the country burned within me. I longed, particularly, to explore the African continent. I pictured myself far, far away, walking down a dusty road, with only my backpack for company. The image brought a sweet sense of relief.

It took about two years to save up the requisite funds. In mid-1993 I took off and spent the better part of a year traveling and volunteering, first in Morocco, then Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali, and other African nations.

The first part of that trip felt like an unwinding. I’d been doing a lot of striving over the past five years. Like any freelancer, I was always hustling, always in search of the next gig. I’d extended myself relentlessly, shoving past my inner resistance, making contacts, following up. It was worth it, I’d believed, to get to do what I loved. But the Brigadista tour had demoralized me to the point where, even a couple of years later, I was still finding my way back to myself.

Now, half a world away from anyone who knew me, my tightly knotted spirit began to loosen. Even Vati’s voice, ever present within me, assuring me I was destined for greatness, began to grow softer.

I remember a moment early in the trip, standing alone in a grove of trees, looking up through the tall, narrow trunks to the deep blue sky. I asked myself who I was without my striving. Who would I be, I wondered, if I was not constantly preoccupied with getting my voice out into the world? What would my life look like?

My Nicaragua travels had led me to write Brigadista. I’d assumed I’d write about this trip too. But I didn’t want the desire to write about the experience to interfere with the experience itself. In that moment among the trees, I promised myself that my only goal for this trip would be to experience it as fully as possible. To stay open and connect deeply with the people, places and cultures I visited. If I ended up writing about it, great. If I didn’t, that would be okay too. As long as I savored every moment, the trip would be a success.

I remembered my fairy god-juggler—the way he’d appeared right when I needed him to help illuminate my path, and how Holly Near’s assistant Judy had popped in almost immediately thereafter. I thought, too, of Vati, and all the different pieces of my life he’d helped me to navigate. Who would guide this leg of my journey?

I guessed I’d have to do it myself.

Stay tuned for You’re Gonna Be a Star Someday, Part 4, coming soon to a Substack near you!

Register for July’s FREE Comfort-in-Community Off-Leash Writing Sessions here.

What a brilliant narrative. I kid myself into thinking I know you, but every time I read something you've written more and more layers of your amazing life as an actress and creator are revealed. One of the most astonishing things about this post came at the very end – I can't believe were both in Mali's Dogon country in 1994! I wonder what month that photo was taken (I was there in February).. We might have even crossed paths in our.super funky Malian taxis!.

Wow, Tanya, I knew you were adventurous, resourceful, and creative, but WOW!!! What an amazing story, and how courageous you always were in following your heart and also doing all the practical hustling!! Great story--great LIFE!!!