Dual Citizen

The country my father fled is now our escape hatch.

Dear Friend,

The personal essay below is very close to my heart. For as long as I’ve been thinking of pursuing Austrian citizenship, I’ve been puzzling over how to tell the story. It means a lot to share it with you today.

Before we dive in, though, I want to invite you to join me for two FREE writing workshops I’m calling STRENGTH IN COMMUNITY, on February 22 and March 7. These sessions are an invitation to come together in these extraordinarily challenging times and find ourselves on the page, separately and together. Writing and sharing our voices in community is a profoundly powerful experience. I hope you’ll join me.

Warmly,

Tanya

And now … Dual Citizen.

Dual Citizen

THE LETTER

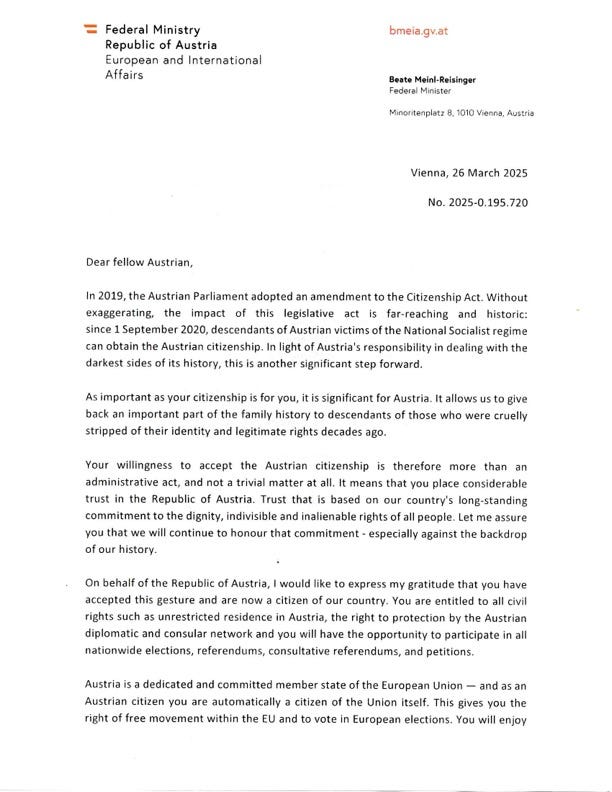

A few weeks ago, I received a package in the mail from the Austrian consulate. Along with a certificate confirming my new citizenship, it contained a letter from Beate Meinl-Reisinger, Federal Minister of the Republic of Austria.

“Dear Fellow Austrian,” the letter began. It went on to describe the recent law allowing citizenship for descendants of victims of the National Socialist regime. As an Austrian citizen, Ms. Meinl-Reisinger wrote, I’m entitled to vote in elections. I’m entitled to the protection of the Austrian government wherever in the world I go.

She expressed gratitude to me for placing my trust in Austria and assured me of the country’s commitment to honor the rights of all its people. The last paragraph read:

It fills me with great pride and joy to welcome you into the worldwide community of Austrian citizens. I hope that this step will strengthen your links to your ancestral home, links that were unjustifiably broken during the darkest hours of our history.

Tears rose. It had been eighty-seven years since my dad fled Vienna.

“I wonder what my dad would think of this,” I wrote to my friend Elena.

“Ask him and listen,” she wrote back.

HOW IT STARTED

My journey to this moment began in mid-September, 2020. It was the height of the Covid epidemic, about a month and a half before the 2020 elections.

One morning, I awoke in my bed and reached for my phone.

“Hey Siri,” I asked, “Can children of Holocaust survivors get Austrian citizenship?”

A headline popped up: “Austria Will Grant Citizenship to Direct Descendants of Austrians Who Survived the Holocaust.”

I’d been thinking of looking into this for at least five years. Unbeknownst to me, the small Jewish community in Vienna, where my father was born, had been working tirelessly throughout that time—and for half a century prior—to pass a law making citizenship possible for people like my children and me.

The date on the article was September 2, 2020. The law had been in effect for less than two weeks.

Goosebumps rose all over my body.

“We could do it,” I thought. “We could leave.”

THAT MOMENT, THEN

As November 3, 2020, approached, I was one of many people threatening to leave the country if the Orange Tick—as my family and I like to call him—was re-elected. Yet even as I spoke of fleeing across the border to Canada, I knew it was just talk. Learning that we could get European citizenship made that possibility a lot more real.

Not that I planned to move to Austria. My feelings about that country remain ambivalent. My Vati (pronounced FAH-tee, German for daddy) always shook his head during the scene in The Sound of Music in which an auditorium full of people sing along to a patriotic Austrian song and grumble about the Third Reich. (We’re big musical theatre fans in my family. They often provide touchpoints for me in navigating the world.)

“The Austrians welcomed the Nazis with open arms,” he told me. “They threw parades for them.” Objectors like the von Trapps were few and far between.

Things are different now, of course, but the far right is on the rise again there, as it is in too many places.

So, no … A move to Austria was not something I’d ever dreamed of. But Austrian citizenship, should we obtain it, would give us the right to live and work anywhere in the European Union. Given the batshit crazy direction the U.S. was headed, having that option felt like a gift.

A fascist government had decimated the community my father grew up in and driven him from the land of his birth. That the same country he’d fled could one day provide refuge to his family against burgeoning fascism in his adopted home seemed darkly ironic. Yet there it was.

JOIN ME?

I mentioned to my older brothers Len and Ron the idea of applying for Austrian citizenship, wondering whether they’d like to do it with me. They expressed vague interest, but no urgency.

“I could do it later if I wanted, right?” said Len.

“Well, yeah,” I said, “but it takes about six months, I think. If we ever need to leave in a hurry, I want to be ready.” The ever-present idea that one might need to leave in a hurry is one of the legacies of being a survivor’s child.

At my wasband’s suggestion (a wasband is a husband from whom one is amicably separated), I contacted a lawyer in Austria. He sent me a list of documents I’d need to gather for the application.

That’s where the story grinds to a halt.

OBSTACLE

I’m intimidated by paperwork under the best of circumstances, and this list felt particularly daunting. It included things like my father’s birth certificate, which I had no clue how to obtain. Of course, the whole point of hiring an Austrian lawyer was for them to research such things for you. Yet even gathering things like my own birth certificate and criminal background check overwhelmed me. I therefore invoked the time-honored mantra, “I’ll do this tomorrow,” and set it aside.

Fortunately, the Red-Yellow Bloodsucker did not win in 2020. And although I still periodically murmured that I needed to get going on that citizenship application, it slid down my list of priorities into the zone of “when I have some time,” alongside the cardboard boxes that have remained stacked in the basement since moving into my house in 2018.

FORWARD MOTION

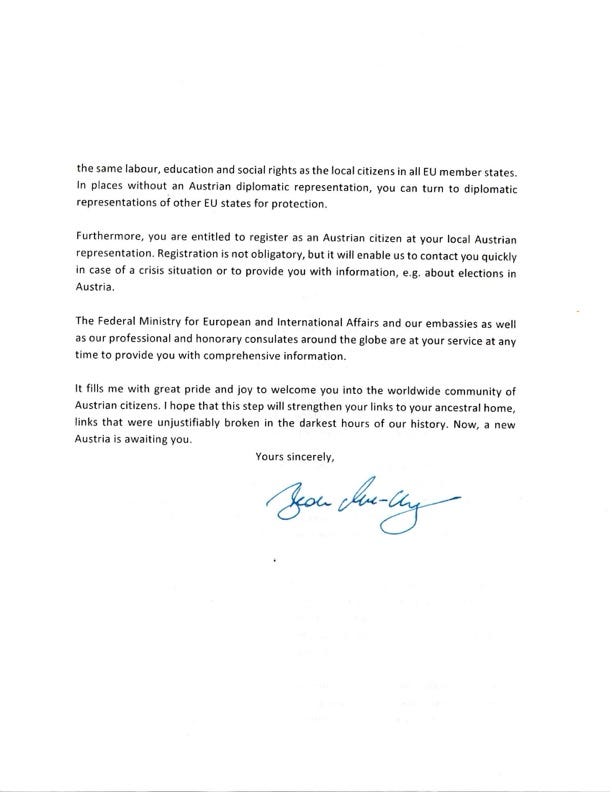

In 2024, the Citrus Sociopath again won the White House. While I sat petrified with shock and horror, my brothers got serious about getting that second passport. Without benefit of lawyer or detective, my brother Ron managed to locate my dad’s birth certificate and an original citizenship document from 1930. My brother Len then set his methodical mind to gathering the other materials and soon submitted his application. Several months later, it was approved.

I was gobsmacked. Here I was the one who’d come up with this idea in the first place. Now my brother was an Austrian citizen, and I was still back at square one.

“So, why haven’t you done it?” Len asked when I pointed this out.

I explained that whenever I looked at the list of documents—which, looking back now, I have to say is not actually very long—something within me froze. For no logical reason, I felt incapable of proceeding.

Then Len did a kind, older brotherly thing. He created a detailed list of every step he’d taken to obtain the documents and submit them. He agreed to be an accountability buddy for me and my brother Ron, answering questions as they arose and cheering us on as we completed the process for ourselves and our offspring.

APPROVED

In January, 2025, I began the process in earnest. In December, citizenship was approved for me and my two sons.

When I learned of the approval via email, I felt … I didn’t know what. This had been so long in the making. And while I’d known we we would almost certainly succeed, as my brother had, I’d somehow never fully believed it. Now that it was a certainty, I felt numb.

I opened ChatGPT and asked what I should feel upon learning that I’d obtained citizenship in the country my father had fled. It informed me there was no particular feeling I should have. Complicated feelings were perfectly natural. It suggested some things I might be feeling, including a sense of restoration but not repair, gratitude tangled with anger or grief, and a complicated relationship to “belonging.”

Although I generally hate AI, I found these words helpful. Allow me my contradictions, okay? You have them too.

Yet although those works spoke to some of what was going on within me—restoration but not repair, gratitude tangled with grief—the numbness persisted.

Then two things happened: ICE agents murdered Renee Good, and I received the Austrian government’s welcome letter in the mail.

BACKGROUND

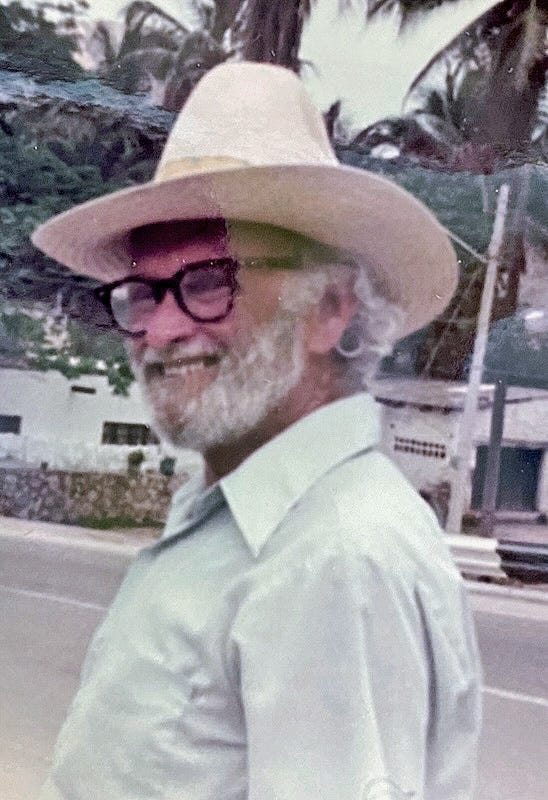

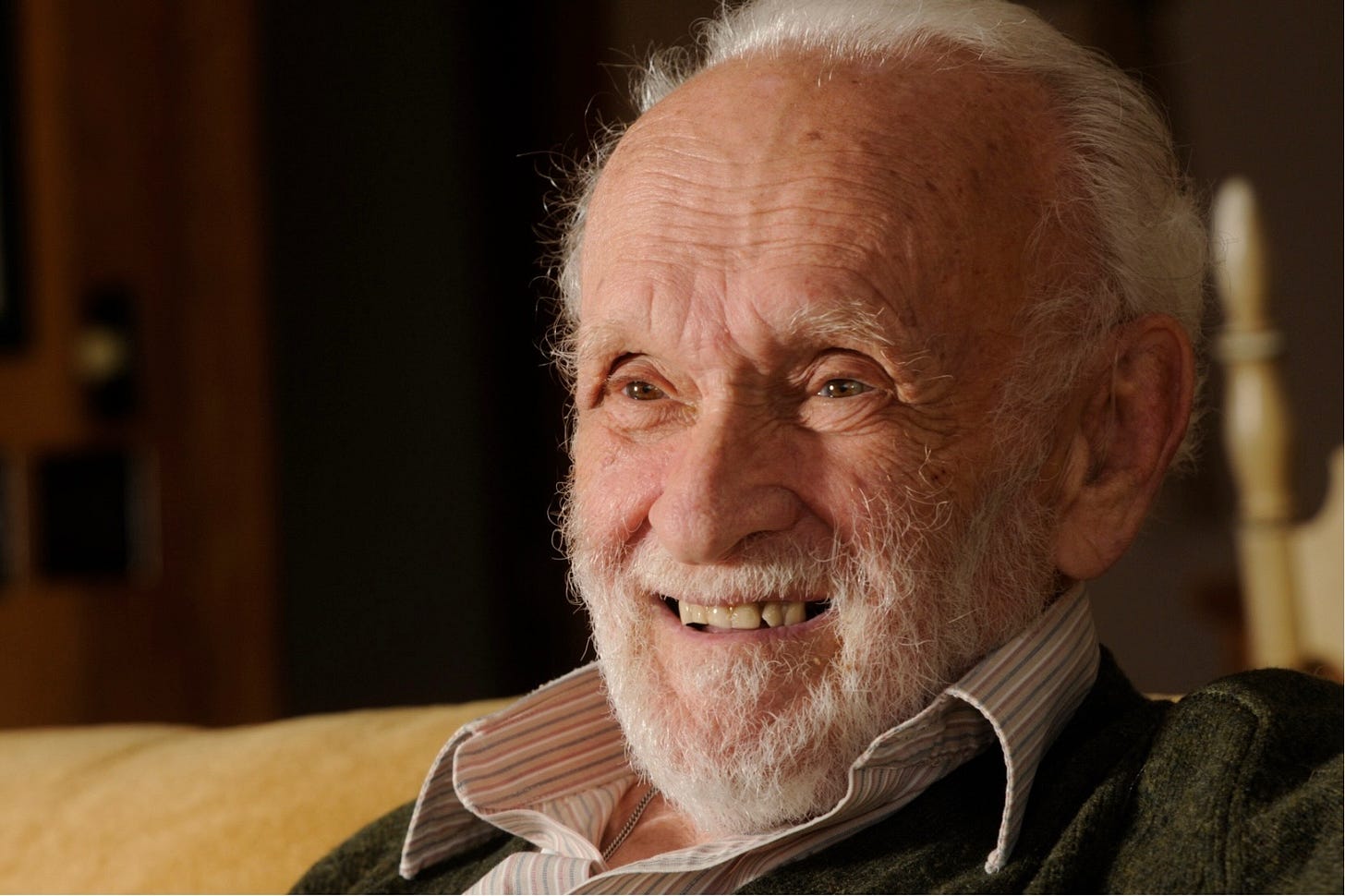

My Vati, Hans Georg Schaffer, was born in Vienna, Austria, on August 28, 1919. He lived there until 1938, when the Anschluss—the German annexation of Austria—took place. He was eighteen years old when cheering throngs lined the streets of Vienna as the Nazi army marched in.

In the early days following the Anschluss, Jews were not only permitted to leave the country but encouraged to do so. They could bring just one small suitcase and the equivalent of about ten dollars in cash. In transferring monetary assets to other countries via the banks, they were allowed to keep just eight percent. The Nazi government confiscated the rest, as well as any property left behind. The intention behind this policy—besides enriching Nazi coffers—was for the departing Jews to create an economic burden on the neighboring countries, making those nations friendlier to the Nazi cause.

Many Jews chose to stay, assuming it would pass. We humans tend not to believe that the very worst will happen to us. My dad’s mother, however, was prescient. She got herself and my Vati out. His father, stepmother (who was not Jewish, but Italian) and grandmother escaped as well. His beloved uncle and other more distant relatives died in the camps. Today, I have only one living family member that I know of on my father’s side, aside from my brothers and our children.

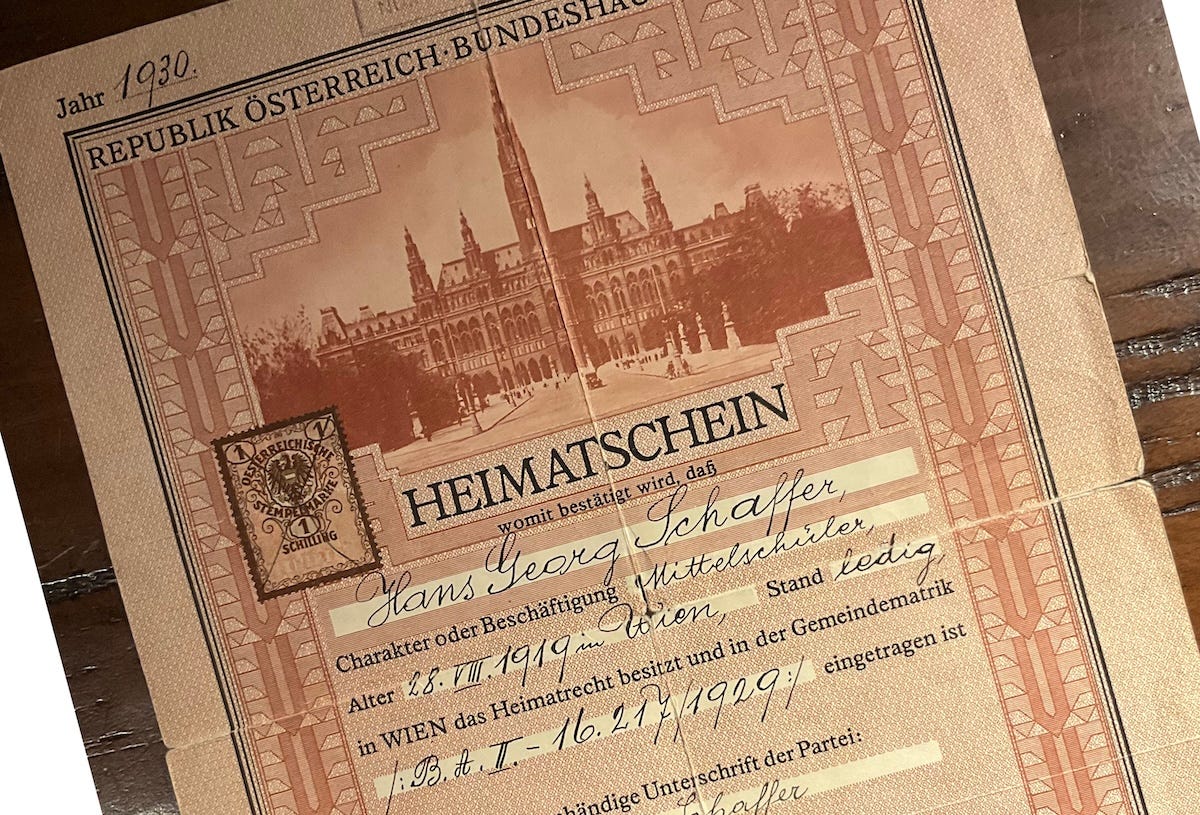

My dad spent time in Italy and Cuba before finally making it to New York in late 1940. When he arrived in this country, he Americanized his name, changing it from Hans Georg Schaffer to Harry George Shaffer, little knowing he’d be condemning his children to a lifetime of saying, “Shaffer, no c.”

The U.S. entered the war shortly after my dad’s arrival, and he joined the army.

“What unit do you think I was in?” he liked to ask people. “Take a guess.”

“I don’t know,” they’d say, perplexed.

“Intelligence, of course!” he’d crow. He’d laugh then, explaining that it wasn’t superior intellect but German-language skills that determined his placement. He worked within the U.S., translating intercepted communications. He was about to be shipped overseas when a jeep he was riding in flipped over, leaving him with multiple broken bones. After months in the hospital, he was honorably discharged.

He attended New York University under the GI bill. He eventually earned a PhD there in economics, leading to a career in academia.

This country was good to him. Very good.

AMERICAN

My Vati loved his new country. That doesn’t mean he thought it was perfect. He was a socialist and an activist. He attended rallies and marches and gave fiery speeches against the Vietnam War. Passionately committed to the Civil Rights Movement, he was one of the leaders of the push to integrate the swimming pool in my hometown of Lawrence, Kansas. During the fifty-two years he taught at the University of Kansas, he acted as faculty sponsor for countless student civil rights and peace groups. He wrote letters to the editor of the Lawrence Journal-World throughout his entire life. He believed civic engagement was a responsibility of citizenship in his new nation. He took it very seriously.

My dad was enthusiastic about the promise of America. He adored the songs of George M. Cohan. He couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket, but he’d march around our living room as the vinyl spun, chanting “You’re a grand old flag, you’re a high-flying flag, and forever in peace may you wave!”

He believed, with all his heart, that Lawrence, Kansas, was the best place on earth that a person could live.

Throughout the 2008 election cycle, my Vati was terribly fearful that Obama would be assassinated. Having lived through the killing of the Kennedys; MLK, Jr.; and Malcolm X, he feared there were elements in this country that would not allow a Black man to become president.

Watching Obama take the oath of office was a profoundly thrilling moment for a man who’d placed racial justice at the center of his adult life.

My Vati died in 2009. I miss him every day. Yet when the Tangerine Monstrosity was elected in 2016, I couldn’t help thinking, “At least my Vati did not have to see this.” That thought comes to me often these days.

PRIDE

Throughout my life, I’ve often felt conflicted about the land of my birth. Thanks to my father’s activism, I was aware from an early age of racial and economic inequality within this country and of American imperialism in Latin America and elsewhere. Still, I wouldn’t be his daughter if I hadn’t also inherited a sense of gratitude towards this country and hope for its potential.

I don’t think I ever felt greater pride in the American experiment than when I first heard the soundtrack of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton.

By writing a musical about the “founding fathers” of the American Revolution in a contemporary urban style and casting it almost entirely with people of color, Miranda and his artistic collaborators created a new American mythology, in which Black and Brown children could take ownership of the American legend and make it their own. It felt like an invitation to reimagine our folklore and co-create a multicultural future.

Lines like “Immigrants—we get the job done” bow to the importance of immigration in creating this nation. But my favorite line, “History has its eyes on you,” pins us to the spot. What will you make of this moment? it asks. When future generations look back on you, what will they see?

It moves me more than I can say. I wish my dad could have seen it.

DUALITY

I first encountered the soundtrack to Hamilton in 2015. In 2016, the Apricot Horror was elected president. Whereas Hamilton had suffused me with pride, the election of a petty, vindictive, hate-filled megalomaniac to the highest office in the land filled me with shame.

I was even more appalled eight years later, when this individual—now a 34-time convicted felon—was elected a second time. And I’m sure I don’t need to tell you, Gentle Reader, that this second term has been far worse than the first.

Yet despite all this, I love this country. Because this country is much more than fearful hate-mongers and ruthless ICE agents. It’s the countless people resisting, standing up for their neighbors, following those agents through the bitter cold, risking their own safety to document atrocities.

I know so many people like that, brave people who work, every day of their lives, for justice and equality. Through direct activism, through the arts, through simple acts of kindness and community care. This, too, is America.

When this thought comes to me, I see my Vati nodding. I see his warm, broad smile.

“It’s true,” he says. “Don’t forget.”

THIS MOMENT, NOW

I have never witnessed a darker moment in this country than the one we’re living in now. In my lifetime, I’ve seen nothing to rival the men in full riot gear patrolling the streets of an American city, dragging people from their homes, cars, and places of work, throwing them in jail, deporting them without due process, murdering them with impunity.

How long will this continue? How many will die? How much further will this president go in trying to impose his will on a shell-shocked world?

Most importantly, how can we stop it?

RESPONSIBILITY

There’s a key difference between my father’s situation and my own. He had to leave Austria to survive. My children and I, on the other hand, are relatively safe here—at least for now.

I ask myself where my responsibility lies. As a person of relative privilege, shouldn’t I stay here and use my voice and what power I have to fight for those most at risk?

Like my Vati, I attend protests and donate money to humanitarian and political organizations. In my writing and my workshops, I try to tell the truth as I understand it and to create spaces for others to do the same.

Yet if I were to leave this country, I could continue to do most of these things from afar.

My boys are still relatively young—seventeen and twenty-two. One of them is autistic and benefits from services this administration is slashing to bits.

Should I persuade them to accompany me and start a new life in a country with nationalized health care, free education, better social services, and far less gun violence? A country that is not run by a narcissistic tyrant who put a vaccine-denier in charge of its department of public health?

Yet my life is here. Brothers, mom, friends, dogs. Language. Community. Home.

At what point does the balance shift? When does leaving become the right choice?

“What should we do?” I ask my Vati.

For now, he just shakes his head and shrugs.

EPILOGUE

The law granting Austrian citizenship to descendants of survivors passed in 2020, eighty-two years after the Anschluss.

As I re-read the letter I received from the Austrian government, I’m moved by what I perceive as the words beneath the words. We wronged your family. We destroyed a community. We are sorry. We cannot erase history, but we can do this.

Will a moment come in which descendants of those being wrongfully detained and deported receive a letter from the U.S. government expressing regret and attempting to make amends? And what of all the others this country has wronged, including Native Americans and the descendants of slaves? Will a time come when they finally receive restitution for what can never be truly repaired?

As remote as such a moment seems from where we sit now, I’d like to believe that, as Eliza sings at the end of Hamilton, “It’s only a matter of time.”

If you enjoyed this essay, you might also enjoy The Exuberant Professor (an introduction to my irrepressible dad), The Night I Made My Father Cry, On Forgiveness, and You’re Gonna Be a Star Someday.

Join me for STRENGTH IN COMMUNITY: two free community writing workshops. LEARN MORE.

I am moved by your story — just having that acceptance letter from the Austrian government must shift the landscape inside you. Selfishly and perhaps naively, I hope your bright spirit remains here. I read straight through without stopping. Thank you.

Wow. Being descended from Sicilian immigrants, with the fact that neither of my mother's parents were naturalized when their children were born here, turns out I'm eligible for Italian citizenship. My cousin, his kids, my sister and her kids did the work and have dual citizenship. My neice lives abroad in Ireland now. The EU makes it possible. Ive wavered. Everything I know is here. My father fought nazis in the Bulge and Germany. I learned to hate fascism from him, and it's become my life-work now.

Italy is governed by right wingers now. It can happen anywhere, even in countries like Germany and Austria who have acknowledged their criminal pasts. Democracy is like Joni Mitchell's paved paradise: you dont know what youve got till It's gone. Powerful read, Tanya.