On Forgiveness

Almost fifty years have passed since a boy whispered "Dirty Jew" in my ear.

Once in the mid-1970s, in the gray-carpeted hallway of my elementary school, a boy whispered Dirty Jew in my ear. I remember the shock of his words and the strange intimacy of his lips so close to my face, his warm breath.

That wasn’t the only time this boy had bullied me in grade school, but it was the only incident I recall in detail. We continued to go to school together all the way through high school, but our circles widened and our paths rarely crossed.

Then, about ten years ago, I got a friend request from him on Facebook.

By that point, most of the divisions from that earlier period of life had dissolved. I was “friends” on Facebook with lots of folks I’d barely spoken to in school. We’d shared a childhood in Lawrence, Kansas, and we’d reached the stage of life where nostalgia rendered that connection inherently meaningful. But though I’d accepted requests from others who’d once been dismissive or even mean towards me, this particular incident—one of only two overtly antisemitic episodes I’d experienced growing up—sat with me differently.

I let the request linger for a few days, then deleted it.

I sit writing this on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, the most sacred day in the Jewish calendar. As a mostly non-observant person of Jewish heritage and upbringing, I’m not fasting. But I can’t help reflecting on the themes of repair and forgiveness this day brings forward.

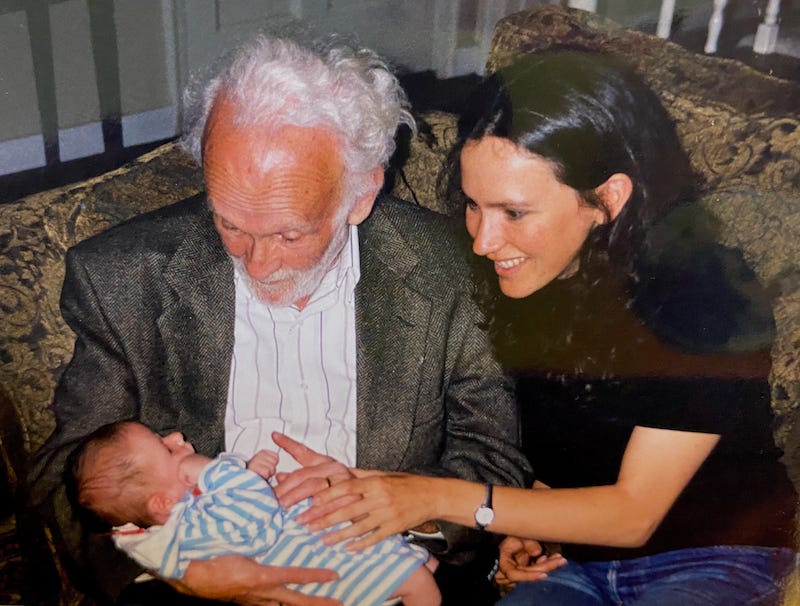

When it came to forgiveness, my Vati (pronounced FAH-tee, German for daddy) was a veritable Anne Frank. He could easily have written her famous words, In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart. Born in Vienna, Austria, in 1919, my Vati was a young man when the Nazis came to power. He lost his home, his country, his beloved uncle, and much more, but unlike Anne Frank, he escaped with his life. In spite of all this, he never lost faith in humanity.

My Vati told me a story from his childhood of meeting a little boy near his grandparents’ apartment who was going on and on about how much he hated Jews.

“Have you ever met a Jew?” my Vati asked him.

“No,” admitted the boy.

“Well, I’m a Jew,” my Vati said.

As he remembered it, the boy just stared at him with an open mouth, not knowing what to say.

My dad immigrated to the US during World War II. Later, he was active in the anti-Vietnam War and Civil Rights Movements. He was deeply passionate in his convictions, and he was always willing to talk about them with anyone who showed the slightest bit of interest. Unlike so many of us today, he liked nothing better than to reach across the aisle to learn and persuade. No matter how extreme a position someone expressed, he never wrote them off. He gave everyone the benefit of the doubt, always believing that people would shed their prejudices if they could just be made to see the humanity of those they considered Other.

In the mid-1960s, he was one of the leaders in a movement to integrate the swimming pool in Lawrence. As a result, someone left a bag of dog shit on our porch. Once a man called on the phone to threaten my dad’s life. Instead of hanging up on him, my dad started asking questions. They ended up going out to lunch. I don’t know if my Vati persuaded that man that integrating the swimming pool was the right choice, but I remain in awe of his willingness to try.

My dad taught economics at the University of Kansas for fifty-four years. He often played cards with a faculty member of German descent. Over time, they became friends. This man had been an officer in the Nazi army.

One night, when my Vati and this man were playing cards, the man got drunk and began to cry. He got on his knees and begged my father’s forgiveness. My dad didn’t know what rank the man had held, where he’d been stationed, or what precisely he’d done. The man would not speak of it. He only repeated, again and again, that he was sorry.

“Young German men were forced to join the army,” my Vati told me. “If they refused, they’d be jailed, sent to a concentration camp, or even executed.”

Some resisted, of course. But most didn’t. It takes a person of extraordinary courage to place themselves at risk for the sake of others. Most of us would like to think that we’d be the ones to stand up in a situation like that. In truth, we can’t know what we’d do in any such situation unless we’ve lived it. We can only hope never to be tested.

I believe my father saw this man as a person of ordinary courage and ordinary kindness who was pinned to the wall by circumstance. I believe he forgave him, and they remained friends.

My father invited this friend of his to attend my bat mitzvah at the Lawrence Jewish Community Center. Most of the members had no idea who he was. One woman, though, also a faculty member at KU, recognized him. She was horrified by his presence and never spoke to my father again.

In the mid-1990s, my dad and stepmom visited Vienna. One day my dad began chatting with a large family at the next table in the restaurant where they were having lunch. When it emerged that my dad was born in Vienna, they asked him why he’d left. He told them he’d had no choice, being Jewish at that moment in history. I imagine he included some version of his usual quip, “As you know, Austria’s a small country, so when Hitler came, it wasn’t big enough for the two of us. He didn’t want to leave, so I had to!”

After my Vati told his story, the family went back to their conversation and he and my stepmom went back to theirs. A short while later, though, the different members of that family, none of whom had been born at the time my father left, approached the table one by one and apologized to him on behalf of their country and its people. They were so very sorry for what he had endured, they said. They wished it had been otherwise and hoped he felt welcomed back.

This was a story my Vati loved to tell, because it supported his worldview and faith in humanity.

I write this in a world at war, in a country on the brink of a crucial election. I write this in a moment when so many of us—myself included—can barely imagine having a real, sustained conversation with someone who supports a candidate we consider so abhorrent that we often feel as though we’re living within a satire. What can we, I, learn from my Vati’s example?

I recently attended my forty-year high school reunion. It was a deeply moving, celebratory event. Everyone was so much warmer, kinder, more open than I remembered them. Which made me realize that I too was kinder and more open, and less judgmental towards them. A friend remarked that she was hearing many stories of amends—people apologizing for things they’d done and said more than four decades ago.

The boy who whispered Dirty Jew in my ear is now a man approaching sixty. I heard through the grapevine that he has suffered profound losses in his life. I also heard that he was one of those who expressed regret for things he’d done long ago.

Close to fifty years have passed since the episode in question. I ask myself what makes a child under twelve say something like that? Did he know what he was saying? Is it even possible I misheard him? And if he did say it, does he remember? From what I’ve heard of who this person is today, I believe that if he did remember, he would be sorry.

My Vati would likely have approached this man at the reunion and said hello. Perhaps they would have talked, embraced, even cried together. But though I aim each day to live into my father’s legacy, I am not him. I couldn’t greet this man without recalling his words in my ear, and I couldn’t bring myself to say, in that noisy, crowded room filled with people laughing, hugging, and drinking, Do you remember the time…? So I did nothing. I saw him across the room and steered clear.

It’s a tiny thing, I know, but in my heart, on this Day of Atonement, I forgive this man, just as I hope those I have wronged will forgive me. I will not contact him, but if thoughts and emotions have the power to create ripples in the actual world, perhaps this one, going forth from my heart, can loosen a knot somewhere, if only in the smallest of ways.

May we be brave and kind. May we see the humanity in the eyes of those we have considered Other. And may we each do what we can, large and small, to create a more peaceful world.

Do you have stories within you that are aching to emerge? I lead Off-Leash Writing Workshops and Memoir & Fictions Workshops to help free your voice and get your words out of your head and onto the page. Learn more at offleashwriting.com and get on my email list to be notified when new sessions begin.

Beautiful sentiments and the photos of your dad are just so telling, a kind man indeed.

Stories were so real and touching; I feel I know him, and what a presence and living spirit your crafted. But that boy from grade school, now grown into a nearly 60 year old man,--- I'd love to talk with him and find out where that hatred came from, and how he rid himself of it---if, indeed he has.

Tanya, this is such a beautiful, painful, but also inspiring piece of writing. Wow. Your father, what a magnificent human. Thank you for writing this. All the best, Yehuda